A spirited conversation about inequality

14 years after the publication of 'The Spirit Level', its authors took part in a thought-provoking discussion about the state of inequality in the UK, and the state of the evidence base

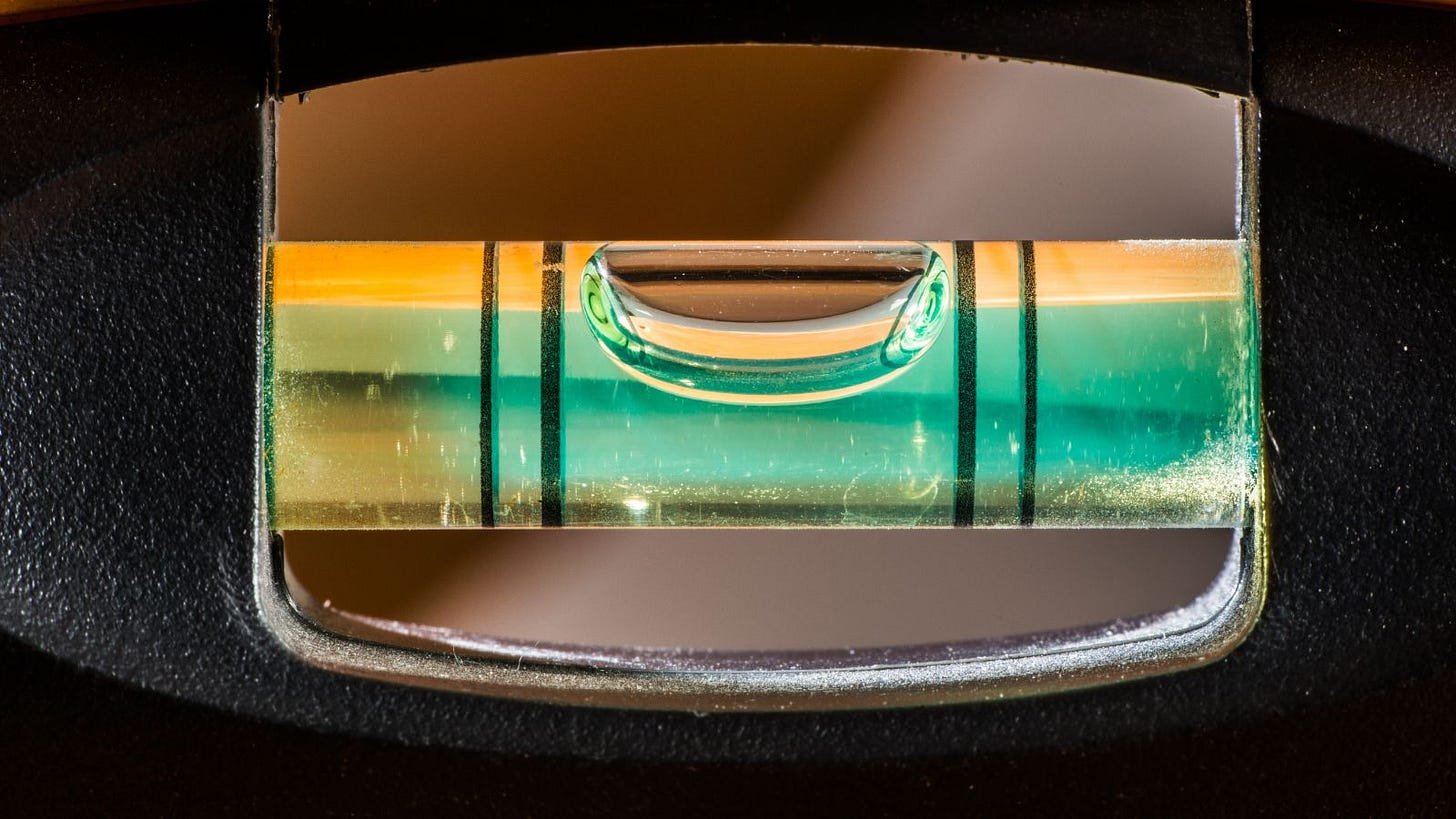

In their influential and award-winning 2009 book The Spirit Level, Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson argued that societies with the biggest gaps between the rich and the rest are bad for everyone, including those who are most well off. They contended that everything from life expectancy, mental illness and obesity to violence and illiteracy is affected not so much by the wealth of a society as by its level of equality.

As part of the Policy Institute and the Fairness Foundation’s Fair Society series, we organised a webinar last Tuesday to revisit The Spirit Level and consider its lasting impact on how we think about inequality, with reference to what has happened to inequality in the UK in the 14 years since the book was first published.

The webinar featured:

Kate Pickett OBE, Professor of Epidemiology, University of York, and co-author of The Spirit Level

Richard Wilkinson, Professor Emeritus of Social Epidemiology, University of Nottingham, and co-author of The Spirit Level

David Aaronovitch, journalist, presenter and author

Lucinda Platt, Professor of Social Policy and Sociology, London School of Economics

Paul Drechsler CBE, Chair, International Chamber of Commerce UK and BusinessLDN, and former President of the Confederation of British Industry

Bobby Duffy, Director, the Policy Institute at King's College London (Chair)

Watch the webinar recording here. Below are some reflections on the event.

Themes discussed at the event

The book played a huge role in putting inequality onto the policy agenda. David pointed to the impact of The Spirit Level on the debate in the UK, and to the value of the global comparisons in the book for a UK debate that can be very parochial. Kate highlighted the contrast between high levels of engagement with inequality issues at the global level (Sustainable Development Goals, World Economic Forum and so on) and at the local level (local authorities in the UK) on one hand, and the struggle to engage with the UK government at the national level on the other hand. Recent events, notably the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, have driven inequality up the domestic political agenda, although it hasn’t yet become a top priority.

The evidence base has grown considerably since the book was published. Kate and Richard published Income inequality and health: a causal review in 2015, and a huge body of third-party research on the consequences of inequality has appeared over the last 14 years, linking it to issues such as domestic violence, narcissism, gambling, low civic participation and child maltreatment, across a range of countries. Other studies have looked at the mechanisms that drive these causal relationships, including the impacts that inequalities of status and respect have on consumerism and on violent crime, as well as on people’s mental and physical health. In the last two years the Institute for Fiscal Studies has published the Deaton Review of Inequality, which examines the state of a wide range of inequalities in the UK (and elsewhere) from a broad set of methodological perspectives.

Inequality in the UK and many other countries has got a lot worse since 2009. David talked about the damage done to our society when so many people are worried about making ends meet, and when a small number of wealthy individuals wield huge amounts of power. Paul spoke about the correlation between postcodes and educational outcomes as an example of unfair inequalities, but questioned whether people in the UK understand the true scale and impact of inequality in this country. Lucinda emphasised the importance of global inequalities, and the impact of the ‘lottery of birth’ (which country someone is born in) on the extent to which their talents and efforts are rewarded.

There’s a more widespread consensus about the damage done by inequality than there was in 2009. Paul spoke about the business case for the private sector to make the arguments for tackling inequality, which is multi-faceted (economic and social stability, consumer spending and growth, access to diverse talent, employee engagement and retention, reputation, licence to operate). There was a discussion about the increasing recognition that unequal outcomes in one generation lead to unequal opportunities in the next, although this is by no means universally acknowledged. The event ended on an optimistic note, with agreement that younger generations are a source of hope, despite all of the barriers to change.