Are young people losing faith in the tax system?

A joint post with Mike Lewis at Taxwatch about some concerning HMRC survey data

I’m delighted to have co-authored this post with Mike Lewis, Director of TaxWatch.

Taxes are the price we pay for a civilised society, so the saying goes. But what if the civilisation that previous generations took for granted looks to have disappeared into the sunset, seemingly never to return?

The expectation that living standards would continue to improve from generation to generation has been cruelly undermined in recent decades, with today’s young people no longer able to rely on secure work, affordable and decent housing, a reasonable pension, even a liveable planet. The social contract is fraying. The impact of this shows up in worsening mental health, in declining faith in democracy, perhaps even in an apparent resurgence of religious belief and practice.

Previously overlooked survey data from HMRC into the public’s attitudes to tax evasion and avoidance suggests that this intergenerational attitudinal faultline might also extend to the tax system.

Research on attitudes to tax tends to focus on attitudes to tax policies, especially around government Budgets and other ‘fiscal moments’, and not on attitudes to tax behaviour. This means that we know quite a lot about people’s opinions of how high taxes should be, and about who and what should be taxed. Sentiment about tax levels varies, but most people – unsurprisingly - want the wealthy and large companies to pay more tax, but don’t think they themselves should pay more.

We know much less about people’s opinions of complying with the existing tax system. Not who should pay and how much, but simply: should people pay their due taxes?

One relevant body of data, though, is HMRC’s annual surveys of UK taxpayers (‘customers’). For several years now these surveys have included questions on the prevalence and acceptability of tax avoidance (“exploiting tax rules to gain a tax advantage”) and tax evasion (“some people don’t tell HMRC about all their income”). They poll individual taxpayers as well as tax advisers, and small, medium and large businesses.

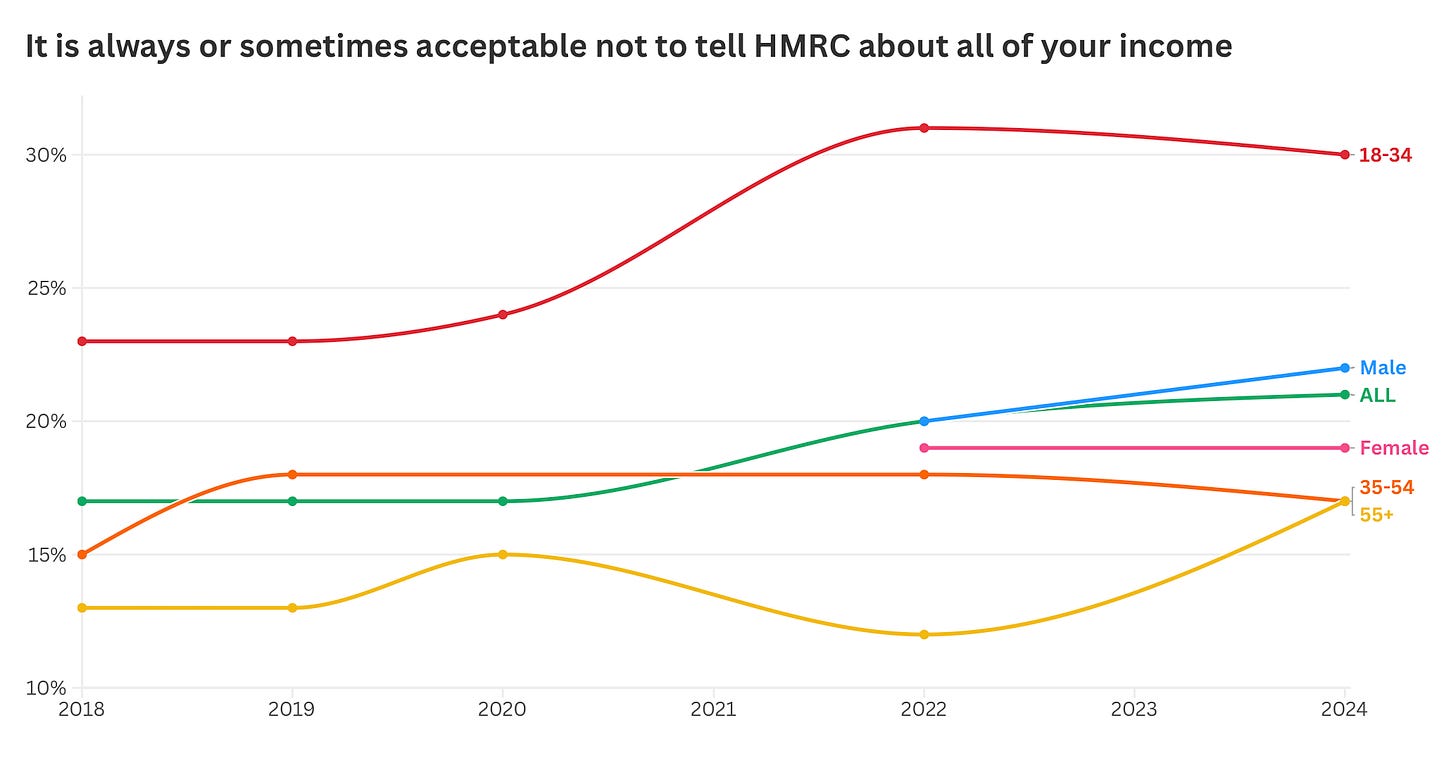

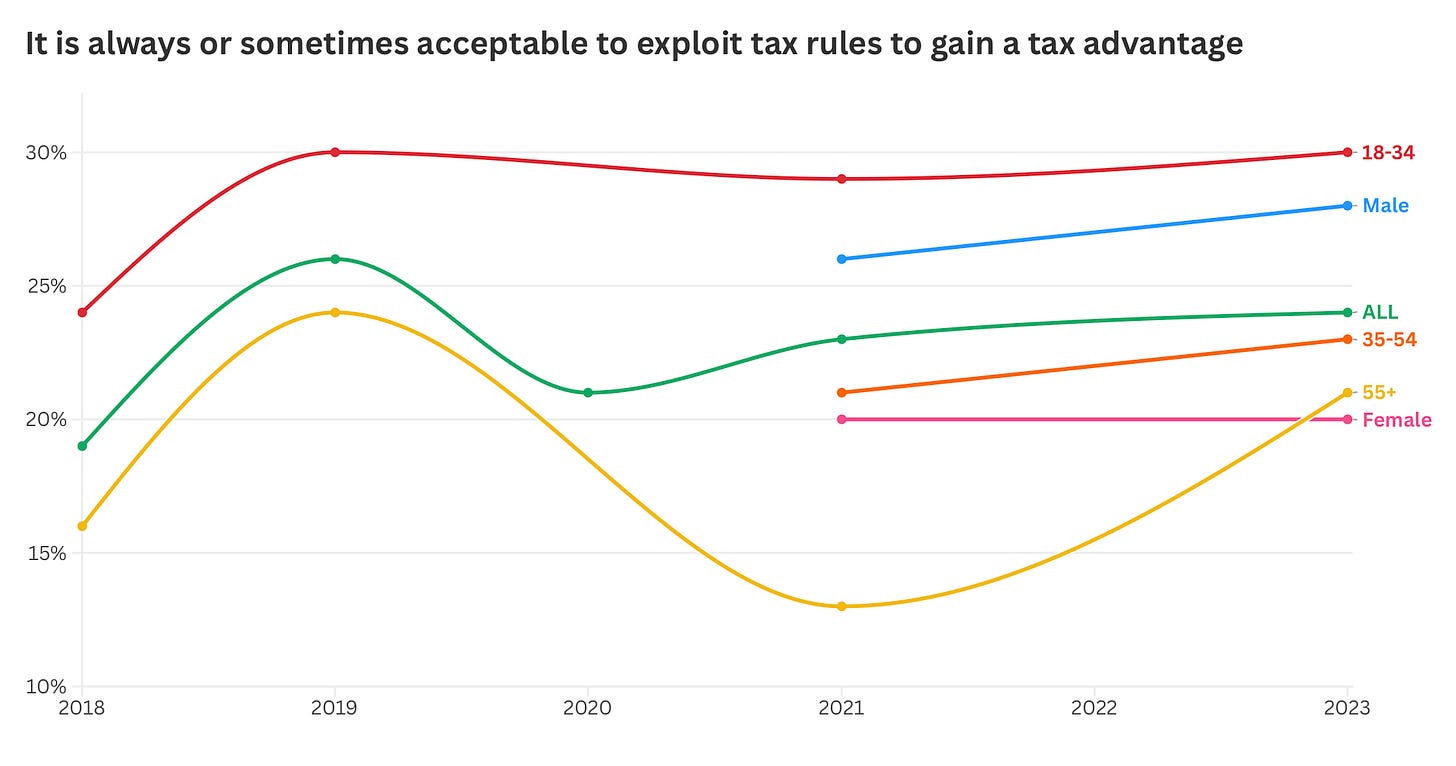

Individuals’ attitudes to tax evasion and avoidance throw up some striking patterns. The most noticeable finding is that ‘tax morale’ seems to be falling across all age cohorts, but is persistently lower - and falling faster - amongst the youngest age cohort.

In 2024, 31% of 16–to-34-year-olds said that it is ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ acceptable for people not to tell HMRC about all of their income (tax evasion), compared to 17% of people aged 35 or above. Back in 2018, only 23% of 16–to-34-year-olds (and 15-17% of older age cohorts) thought that this was ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ acceptable.

Similarly, in 2023, 29% of 16–to-34-year-olds said that it is ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ acceptable for people to exploit tax loopholes (tax avoidance), compared to 21-24% of people in older age cohorts. In 2018, only 24% of 16–to-34-year-olds thought that this was OK, compared to 16-19% of people over 35.

A gender breakdown has only been published since 2022, but this shows a significantly higher level of acceptance of both tax avoidance and tax evasion among men than among women.

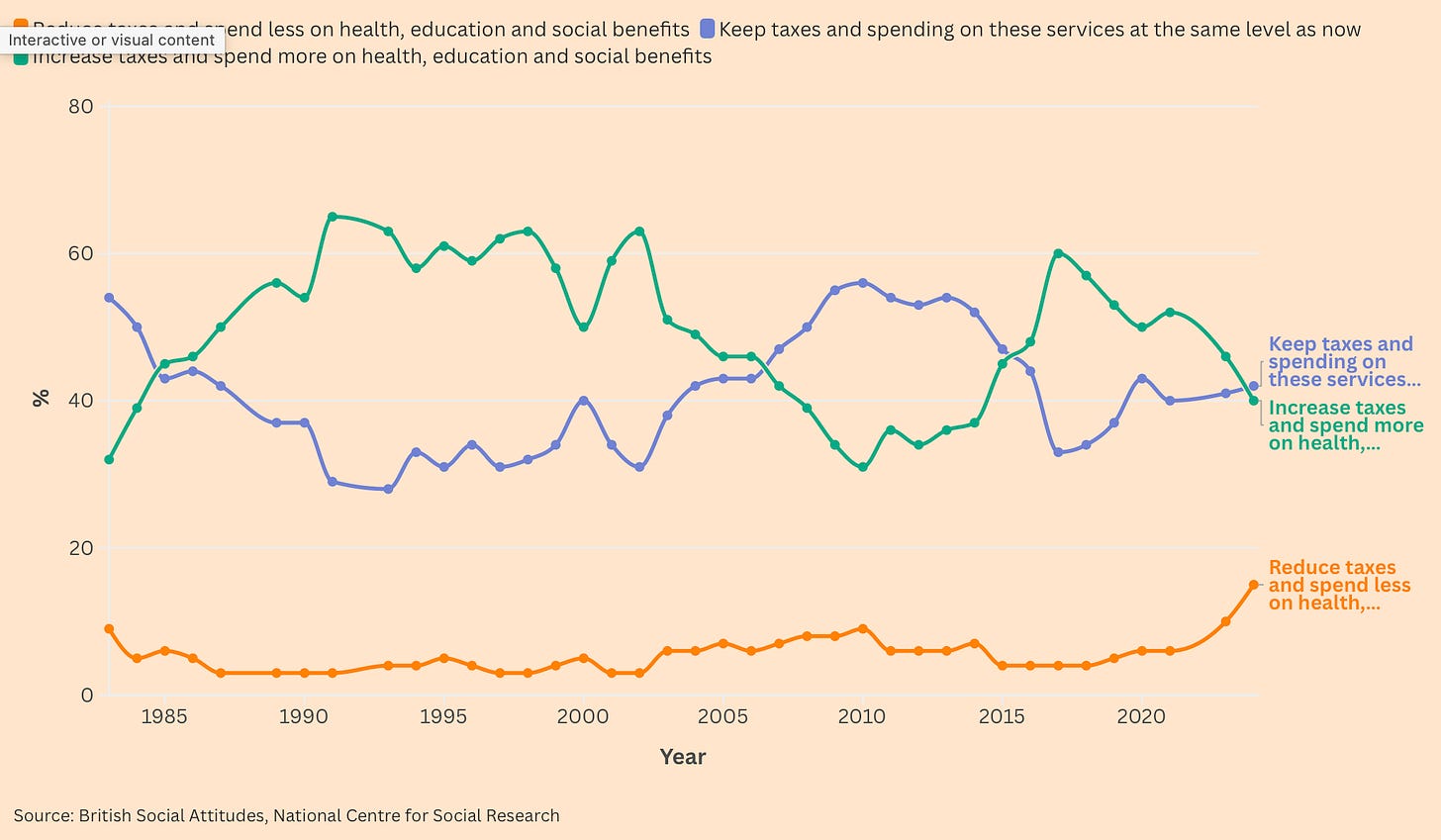

Public attitudes to tax and spending in the UK are normally ‘thermostatic’. People react to lower taxes, spending cuts and poorer public services by increasing their support for tax-and-spend policies, but swing back to supporting tax and spending cuts after a period of higher tax-and-spend which has led to improved public services. This contrasts, for example, with public attitudes in many Scandinavian countries, whose tax systems enjoy strong support despite high levels of taxation because they pay for strong public services that are often universal and wide-ranging (e.g. universal free childcare).

Could the latest HMRC data suggest that public attitudes to tax have moved in the opposite direction from the Scandinavian ‘virtuous cycle’, towards a ‘vicious cycle’ where public services - and the broader legitimacy of the state and the social contract - have frayed to such an extent that a growing minority of taxpayers, particularly among the newest generation, no longer believes that paying tax is necessary if you can get away with not doing it?

There’s some evidence for this from the latest British Social Attitudes survey, which has tracked public attitudes to tax and spending for forty years. Taxing and spending more is still much more popular than taxing and spending less: 40% of people would like to raise taxes and spend more on health, education and social benefits; compared to only 15% who want less tax-and-spend. But that 15% is the highest that it has ever been since the survey started in 1983. Between 1990 and 2020, support for lower tax and spending bubbled along at between 3% and 9%. It’s seen a large uptick since 2021.

One obvious interpretation is that this rise in opposition to current levels of tax and spend is just the normal ‘thermostatic’ reaction to the expansion of the British state since the pandemic. But the unprecedented level of this sentiment, alongside a widespread feeling that the state is not over-funded but crumbling, suggests that something new may be going on. To tell us what is driving these sentiments, we need more work on the social, age and gender breakdown of these opponents of tax and spend – but the trend is clear.

Of course, younger people (/voters/taxpayers) get less out of the tax system than their older peers, because they are less prolific and expensive users of public services, not least the NHS, which is bound to have some impact on how they think about paying taxes. And comparing attitudes to tax avoidance and evasion between age groups is complicated by broader differences in political attitudes between those groups, as well as the contrasting views of young men and young women.

Nonetheless, there’s clearly something more at play here, and it seems reasonable to assume that the fraying social contract has a key role to play in reducing the support of younger generations for the tax system. People are getting less civilisation in return for their taxpayer pound.

The problem is likely exacerbated by the strong public perception – not unjustified – that the wealthy are not contributing their fair share of tax revenues into the system. This dynamic is compellingly illustrated by recent research from the London School of Economics, in which an experiment undertaken with 4,000 survey respondents in the US found that when people are made aware that the super-rich pay lower total tax rates than the rest of the population, they are more supportive of raising taxes on the wealthy, but less supportive of taxes on the middle classes. In other words, because low taxes on billionaires are widely considered to be unfair, this in turn undermines support for broader-based tax rises. If those with the broadest shoulders are not paying in their fair share, why should everyone else have to pay more?

Whatever is driving these patterns of taxpayer sentiment, the HMRC data on attitudes to tax dodging contain a warning for politicians. Without urgent action to improve public services and the social contract, alongside steps to ensure that the richest are paying their way, there’s a real risk that public consent not just for raising more revenues to fix the UK’s crumbling public realm, but for complying with tax obligations at all - starts to dip into dangerous territory over the coming years.

The connection between perceived fairness (super-rich paying lower rates) and broader compliance is crucial. The LSE research finding makes intuitive sense—when enforcement feels selective, reciprocity breaks down fast. I saw a simlilar dynamic play out in another country's VAT compliance where small businesses started cash transactions more after high-profile cases of wealthy individuals getting settlements. The thermostatic model usually assumes people trust the basics are working.