Fragmentation nation

Inequality and meritocratic myths feed off each other, undermining concern about inequality and support for action to tackle it

Today sees the biggest strike in the history of the NHS, and the first time that nurses and ambulance staff have walked out on the same day.

Last Wednesday, our report Striking A Nerve explored some of the reasons why different people supported or opposed strikes by various groups of workers, by asking how much they agreed or disagreed with a range of ‘fairness’ arguments for and against strikes. In summary, we found a large majority in favour of most of the pro-strike arguments, including most Conservative voters, with slightly less support for most of the anti-strike arguments, while support for the strikes themselves was very variable depending on who we asked and which group of workers we asked about.

If you had a chance to look at the report and have any feedback on it, I'd be very grateful for your thoughts via our online form - it will only take a couple of minutes. Thank you!

The day before we published our report, YouGov published some polling results about what affects support for the strikes, which found that “support for strike action correlates strongly with workers’ perceived contribution to society and whether they are underpaid, but not with disruption caused”.

Although they do not mention it in the article, it is clear from YouGov’s full results that there are big differences among Conservative and Labour voters, unsurprisingly. And the academic literature suggests that public attitudes to trades unions more generally are heavily conditioned by political beliefs. A 2022 study of some psychological determinants of broad union attitudes in the US and Canada found that lower levels of support for unions were highly correlated with “stronger political conservative orientation, prejudice feelings towards union members and less accurate knowledge of union activities”, but less so with “meritocratic and social mobility beliefs”. However, the last finding is slightly at odds with a 1984 paper on The Protestant Work Ethic, Voting Behaviour and Attitudes to the Trade Unions (never let it be said that we’re not bringing you the latest cutting-edge research), which found clear links between people’s beliefs in the Protestant work ethic and their views on trades unions.

If we take a step back from thinking about strikes and trade unions, and cast our gaze across society and the economy more broadly, I think you could argue that, in our highly unequal and rather fragmented society, a set of self-reinforcing myths are undermining social cohesion and empathy. These two trends feed off each other - as inequality deepens, empathy atrophies, laying the groundwork for ever-deepening inequality. Perhaps this helps to explain why people are less supportive of striking workers who don’t benefit from the ‘halo effect’ of the NHS and, to a slightly lesser extent, schools. We seem to have already forgotten the lesson that we learned the hard way during lockdown - that a wide range of people on low incomes do work that is critical to keeping our society and economy functioning.

I first came across the argument that inequality and lack of empathy reinforce each other in the work of the Dutch sociologist Jonathan Mijs, who is based in the US but is a Visiting Fellow at the International Inequalities Institute at LSE. In The Paradox of Inequality: Income Inequality and Belief in Meritocracy go Hand in Hand, he shows that higher levels of (income) inequality lead to lower levels of concern about it. How to explain this paradox? His view is that “the more unequal a society, the more likely its citizens are to explain success in meritocratic terms, and the less important they deem nonmeritocratic factors such as a person’s family wealth and connections”. In other words, as inequality increases, people are more likely to tell themselves that some or all of this inequality is ‘fair’, because it has somehow been ‘earned’. “Unequal societies create conditions for their legitimation”, as Mijs puts it in a seminar slide deck.

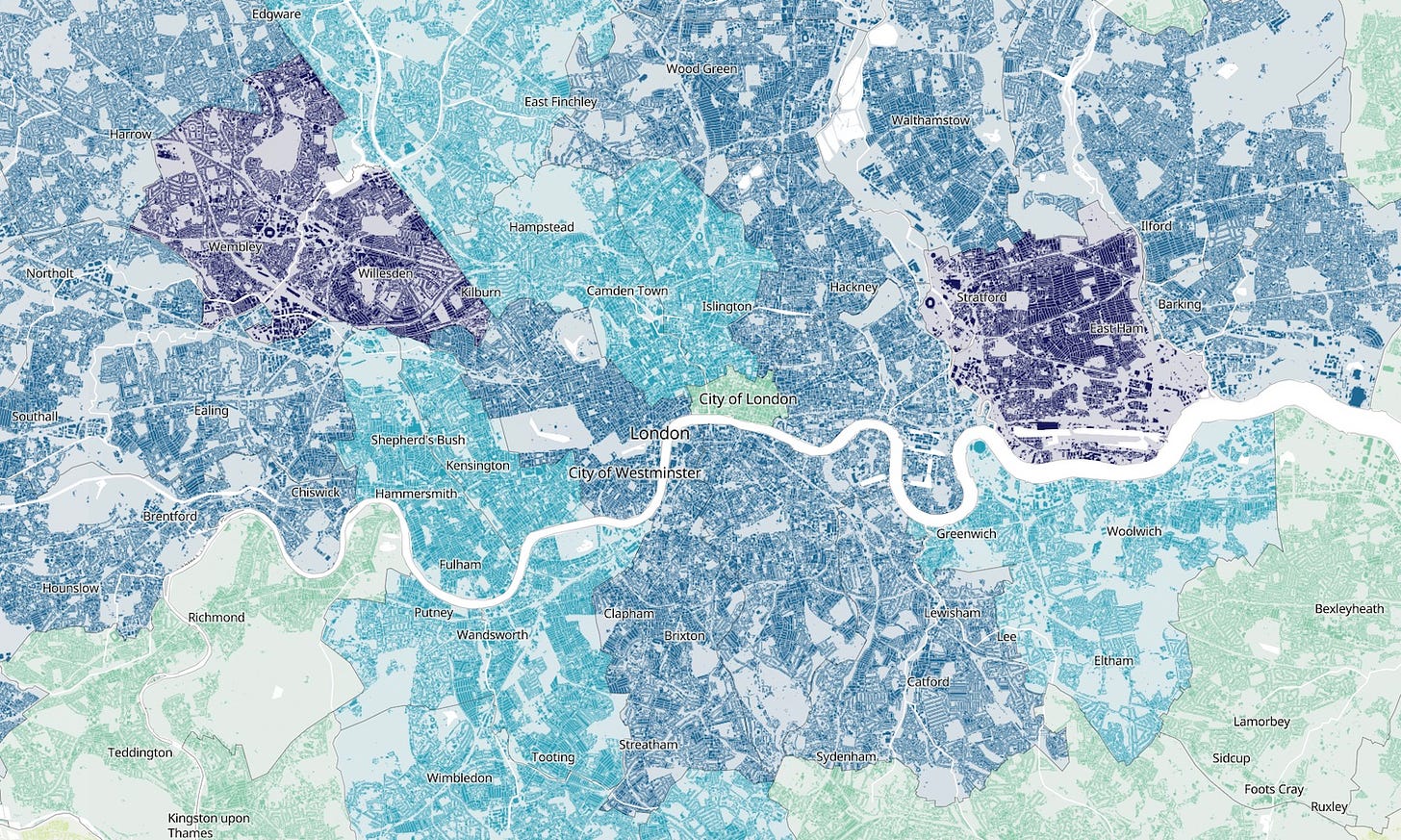

There’s a third, key dimension to his argument: social distance. Polly Toynbee outlines the theory in an article about his paper: “As countries get more unequal, people live in greater social isolation, locked within a narrow income group. Their friends and family share the same incomes, are segregated by neighbourhood and marry similar partners. Children mix less in socially segregated schools. People no longer see over the high social fences, so they don’t know how the other half lives.” And of course this links to the increasing awareness that inequality manifests itself in social and relational terms, as well as purely economic terms - that we are dealing with inequality of respect, and esteem, and self-esteem, as argued by Michael Sandel in The Tyranny of Merit (we did an event with him in November 2021) and by Elizabeth Anderson.

What to do about all of this? As Mijs points out, there’s a role for providing information to correct misperceptions and to increase awareness of inequality, but while this can raise concerns and preference for redistribution, it can also raise concerns without changing policy preferences, or can even backfire by normalising inequality and therefore reducing levels of concern about it. Social segregation obscures non-meritocratic causes of inequality, and disguises the true extent of inequality to rich and poor alike. So perhaps the best way to break the feedback loop is to find ways to reduce social segregation, for example by increasing interactions across socio-economic divides?

Jon Yates writes in his book Fractured about “why our societies are coming apart and how to put them back together again”. He proposes bringing in three mandatory programmes in the UK, in order to “build a new ‘Common Life’ that can strengthen the glue that bonds our societies”: a four-week national service programme for teenagers (building on the existing National Citizen Service), a parenting programme for new parents, and a national retirement service. Maybe we should encourage teenagers to do a one-week ‘exchange placement’ with a family from a very different part of the country, helping them to build bridges across divides not only of geography but also of class, race and culture?

Plenty of people are thinking about these sorts of issues. There’s a read-across to the levelling up agenda, of course. Onward and Create Streets looked at some of the solutions in May last year at Restitch: The Social Fabric Summit. To take one example: what if we designed buildings and cities to encourage rather than reduce the amount of contact that people have with each other, to deliver quick wins for social cohesion (and maybe slower wins for empathy and mutual concern)?

It’s easy to exaggerate the extent of the schism in our society. There is lots of common ground, as we found when we polled the public on The Fair Necessities. But we urgently need to recognise the vicious cycle that connects inequality with social segregation, and to think about creative ways to tackle it.

PS: a couple of mentions this week. Firstly, Professor Geraldine Van Bueren KC has created a petition proposing that the government should ban discrimination on the grounds of social class. Secondly, two websites that help people to navigate the cost of living crisis - Together Through This Crisis (which also has a campaigning component), and MyPickle.