Guaranteeing the fair essentials

A new campaign is calling on the government to peg benefits to a minimum acceptable standard of living. The fairness arguments for this are hard to disagree with.

Humans have an innate expectation of fairness that evolved thousands of years ago. Evolution through natural selection favours animals that look after their own self-interest, but humans flourished by building large social groups that depend on co-operation, which is sustained by fairness: equalising rewards across a group, sharing resources fairly and punishing selfish behaviour. This is cross-cultural, and children can understand it before they can talk. We are the only species that routinely chooses to help others and reacts strongly to perceived injustice. We have strong instincts for procedural fairness and for reciprocity, but also for ensuring that everyone has their basic needs met and has a fair chance to succeed. Societies that do not uphold this inbuilt sense of fairness become more divided and turbulent, and less successful.

The Fair Necessities, 2021

Fairness is multi-faceted, and the different facets interact with each other. People have a strong sense of reciprocity (what we call fair exchange) - that people should contribute to society as far as they can, and in return should expect to be supported by society when they need it. People should be fairly rewarded for those contributions, and they should expect to have fair opportunities to pursue their goals, and to be fairly treated. But all of this is conditional on the assumption that people’s basic needs are being met - that they have the essentials.

And increasing numbers of people in Britain are unable to meet their basic needs. The phrase ‘heating or eating’ has lost its power to shock through overuse. Even before the cost-of-living crisis struck, the number of people living in ‘deep poverty’ (more than 50% below the relative poverty line) had increased by 52.5% over the previous 25 years, from 2.6 to 4.1 million people (see also our analysis in the Fairness Index). Today, 90% of people in deep poverty are working-age adults or children. Meanwhile the latest government fuel poverty figures show that one in three households in England are having to spend more than 10% of their income (after housing costs) on energy, up from one in five households in 2021.

It’s blindingly obvious that millions of people are going without the basics through no fault of their own, at the mercy of systemic issues - inadequate benefits that have fallen to a 40-year low in real terms, low-paid and insecure work, ever-increasing housing prices and massive increases in the costs of energy, food and other essentials. The Trussell Trust, which runs the biggest network of food banks in the UK, gave out almost 1.3 million parcels between April and September 2022, and says that the main driver of increased need for food banks is inadequate social security.

The latest figures from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Trussell Trust suggest that 90% of low-income households on Universal Credit are going without essentials such as food, utilities and toiletries.

The two charities have come together to propose an essentials guarantee, under which the government would ensure that people on Universal Credit have a minimum level of benefits that allows them to afford the basics.

This level would be determined by an independent process, based on the cost of essentials such as food, utilities and vital household goods. It would ensure that a standard allowance of Universal Credit would at least meet this level and that deductions could “never pull support below this level”.

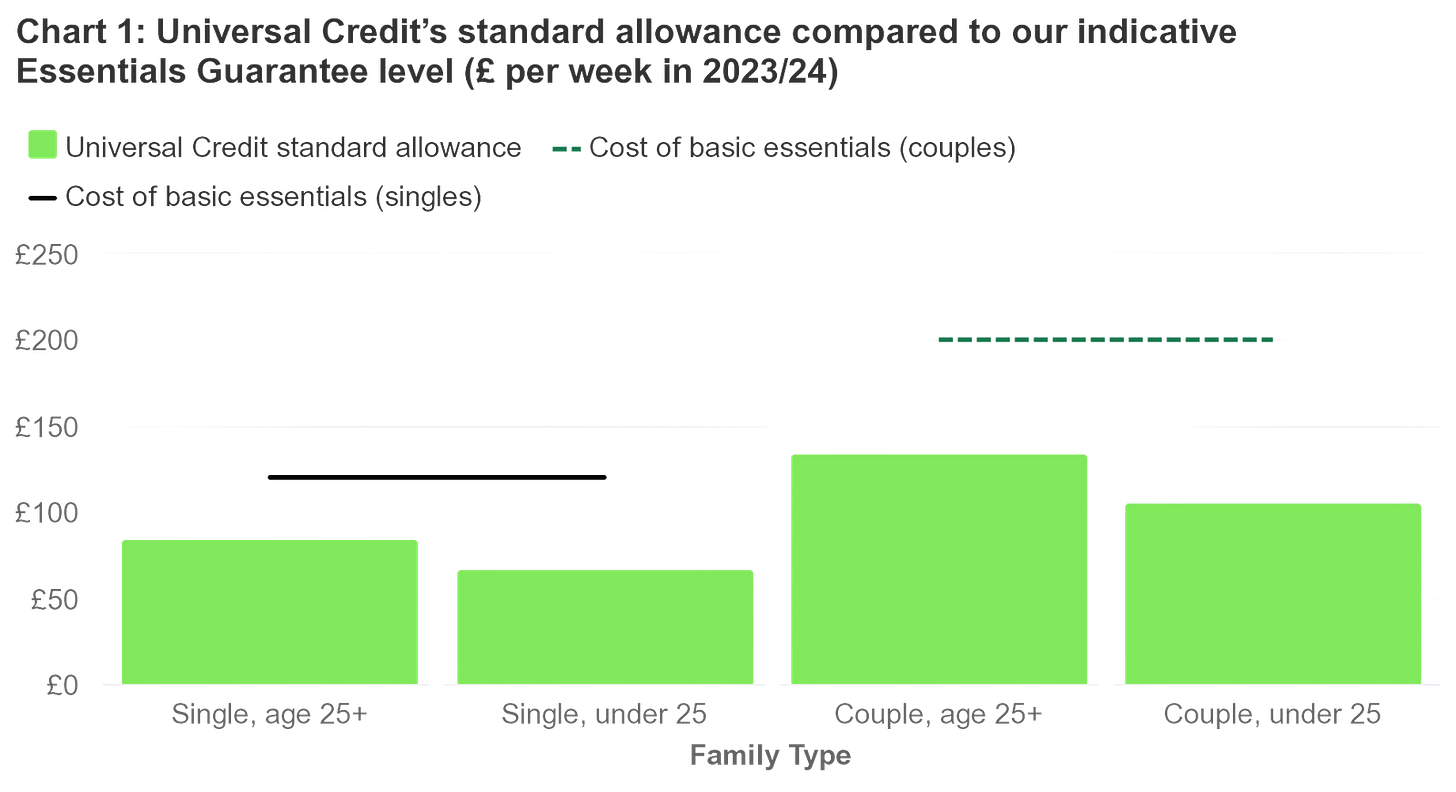

The charities estimate that the cost of essentials is £120 a week for a single person and £200 for a couple. By contrast, the standard allowance of Universal Credit is £85 per week for a single person and £135 for a couple (but over half of households on Universal Credit receive even less than this because of monthly caps and benefit deductions). The chart below gives a graphic depiction of the shortfall.

This is a call for basic levels of fairness in our society to be restored, and for the rebuilding of the social contract. It recognises that we all need support from the state at different points in our lives; some need more support than others, but anyone’s circumstances can change dramatically and quickly for reasons outside their control, such as losing their job, needing to care for a sick relative, or the breakdown of a relationship. The state can and should play a role in reducing the impact of ‘unearned bad luck’ on life chances and outcomes, as we argued in The Fair Necessities. How can we expect people who can’t afford the basic necessities to find a job, or look after their families? You can’t achieve any of the other aspects of fairness - opportunities, reward, exchange and treatment - without the essentials.

Polling to launch the campaign finds that 66% of those asked think the basic rate of Universal Credit is too low, while 67% don’t think they’d be able to afford the essentials if they were on Universal Credit (a recent survey by UnHerd and Focaldata found that 62% of Britons are worried about affording basic necessities, such as food and energy). The polling also found majority support for raising universal credit basic payments, even among 2019 Conservative voters (62% backed an increase). 72% of Britons support the essentials guarantee, while only 8% oppose it.

When we surveyed people about fairness last year, we found that 62% agreed that the government wasn’t doing enough to ensure that everyone is able to meet their basic needs, while 76% agreed that “everyone should have their basic needs met so that no one lives in poverty, and everyone can play a constructive role in society”.

What is interesting is that attitudes to poverty seem to be slowly changing as the number of people unable to afford the basics increases (and as the public become more aware of this phenomenon). Research carried out in recent years by the Policy Institute at King’s College London for the Institute of Fiscal Studies and for Engage Britain has shown that most people believe in meritocracy, but that there are splits between ‘structuralists’ who think that “systematic features of social arrangements create and perpetuate inequalities” and ‘individualists’ who believe that “outcomes are determined entirely by individual efforts”. This translates into much lower levels of support for increasing redistribution through the tax and benefits systems than might otherwise be expected, because people “want to support those who have been denied opportunities, but not those who they believe are not taking up opportunities”.

What’s changing is that more people are coming round to the view that their peers who are using food banks are not their by choice or because they deserve to be there, but because they are being denied the ability and opportunities to live anything like a normal life. A recent article by Sam Freedman argues that the mentality of the electorate has changed from the 1990s because most voters have become poorer in real terms over the 15 years since the financial crisis, and while people still think about fairness in contributory terms, more people now think that wealth inequality is a key part of the problem than pin the blame on immigrants or people on benefits. Attitudes are softening so that the ‘strivers vs skivers’ rhetoric has lost its bite. As the Policy Institute argue: “People are convinced of the need or societal duty to meet people’s basic needs, such as food and housing. In some cases, the public afford equal weight to a wider set of opportunities beyond simply fulfilling basic needs, such as providing access to education.”

In this context, political parties are behind the times. The political consensus of recent decades that has protected the living standards of pensioners has neglected the needs of working age people and children; instead, it has actively worked against their needs by making the benefits system as punitive and inadequate as possible, in order to push them into work that is often poorly paid and insecure. Beveridge called for a ‘national minimum’, instead of setting benefits levels arbitrarily based on political calculations alone. We already have an evidence-based approach for setting the national minimum wage; why not use a similar approach to calculate the minimum level of benefits?

The essentials guarantee would be expensive - the charities estimate £22 billion per year - although they claim that this would lift 1.7 million people (including 600,000 children) out of poverty, and would generate savings by reducing demand for NHS services and other social benefits. It is not, and cannot be, the only approach; a group of charities have formed Together Through This Crisis to call for action on a range of cost of living policies such as help with energy bills, free school meals, and housing benefit, and we need to reform the housing system and deliver better public services at the same time. But these investments will deliver huge social and economic benefits over time. We can’t afford to say that we can’t afford them.