How to create a fair society

Can the left and the right find common ground? Reflections from our webinar last week with Daniel Chandler, author of 'Free and Equal'

Last week we were delighted to co-host a webinar about whether and how the left and right in the UK can find common ground on how to create a fair society:

How do politicians from the Conservative and Labour parties think about what a fair society looks like?

Are their differences intractable, or are there areas with as-yet unrealised potential for cross-party consensus?

If we can find common ground between the fairness principles and priorities of those on the left and the right, what might this look like in terms of concrete policy solutions?

In his new book, Free and Equal: What Would a Fair Society Look Like?, Daniel Chandler builds on the philosophy of John Rawls to argue for a society that protects free speech and transcends culture wars, limits the influence of money on politics, and builds a more just economy that operates within the limits of the planet.

In partnership with the Policy Institute at King’s College London, our partners on the Fair Society event series, we brought Daniel together with Labour MP Anneliese Dodds, Conservative MP John Penrose, and Ryan Shorthouse of Bright Blue to debate these questions. The event was chaired by Suzanne Hall at the Policy Institute.

EVENT RECORDING

DISCUSSION SUMMARY

Daniel Chandler

Neoliberalism has been discredited, so we have an opportunity to shape a new political consensus, but the mainstream political parties are struggling to define it in the absence of intellectual reference points. However, the ideas that we need are hiding in plain sight in the work of the philosopher John Rawls [see our post below for an outline of his key principles].

These principles can bridge political divides in two ways: by articulating an inclusive liberalism that respects different ways of living, and by recognising the value of market-based economies while insisting that their benefits are widely shared. Meritocracy is not enough, and Rawls points us towards a constructive alternative. He also makes clear that we need to think about the distribution of power and control, and about equal opportunities for dignity and self-respect, as well as about inequalities of wealth and income.

How to put those principles into practice is more complicated and perhaps divisive, but the principles point us towards clear policy proposals, such as capping donations to political parties, providing universal early years education and abolishing private schools, introducing some form of universal basic income, doing more ‘predistribution’ to increase incomes and share wealth more equally, and shifting the balance of power between workers and owners.

Anneliese Dodds MP

Most people agree that society is unfair and that we need to fix it; there is also more of a consensus today than there used to be that there is a society at all, and that collective action can achieve real change. We need to tackle inequality in all its forms; no one in politics is happy with the status quo in terms of poverty, destitution and (for example) racial and gender inequalities, but views differ on how to overcome them.

Applying Rawls’s framework is a really interesting exercise, but it is hard for many people to adopt his ‘veil of ignorance’; however, we can achieve change by making the argument that equality will benefit everyone regardless of their position in society (for example by improving productivity), and pushing back against the ‘zero sum’ idea that helping one group will hinder others. We need to promote the plentiful evidence that improving opportunities for some groups helps everyone in society.

John Penrose MP

Daniel’s book points us towards lots of potential areas for consensus between left and right. There is already a consensus about the basic liberties principle, but not so much on the practical changes needed to achieve it, with lots of disagreement about constitutional reform. There is more potential for cross-party consensus on economic issues. And the just savings principle (intergenerational fairness) is really important, because of net zero in particular - an area where there is consensus on the ‘what’, even if there are debates about the ‘how’. This principle can also help us to work out a fair approach to reforming the welfare state to tackle the demographic time bomb that will make it insolvent from the mid-2030s onwards.

There is huge potential for consensus around fair equality of opportunity; the APPG on Inclusive Growth is talking about this in terms of opportunity and agency. This agenda is not just about getting rid of barriers to opportunity, but also about equipping people with the skills and ability to grab those chances, creating agency via education, cultural attitudes and so on. In practical terms this involves policies such as lifelong learning and sovereign wealth funds.

The difference principle is more divisive; it sounds to those on the centre-right like a lot of state intervention that will slow down growth. The right has ceded ground to left on the debate about poverty, and while the left argue that poverty is all about inequality of income, the right needs to push back and argue that it is more complicated and that while a basic level of income is essential, we need to do a lot more than redistributing income to help people to get out of poverty.

Ryan Shorthouse

Rawlsian principles are quite compelling and Conservatives should be broadly comfortable with them, despite questioning the ‘veil of ignorance’ approach used to reach them.

The book offers a spirited defence of the liberal tradition - in the broader sense that emphasises the importance of community and not just the free market - and shows (per Isaiah Berlin) that we need to balance difference social goods such as liberty and security. However, we haven’t actually lived in a neoliberal state in the last forty years, since the size of the state and levels of tax and benefits are at record highs.

The book proposes policies that fit within a liberal framework but might also appeal to the right, such as arguing that hate speech laws might have gone too far, proposing a national citizens service, and suggesting that we need to limit immigration because uncontrolled immigration can hurt the least well off in society. The proposals on democracy in the workplace also have potential for common ground, appealing to the left because of their focus on democratising power, while those on the right could support them because they will lead to increased asset ownership.

People on the right see fairness through the prism of what people deserve - allocating resources based on merit more than on need. We can build policy frameworks that are more contributory, rewarding effort while also meeting basic needs. Crucially, they should reward both economic and social contributions, and there are many practical ways in which this can be done, such as by reforming social security to more closely mirror the social insurance models used in many European countries.

Q&A

In response to a question about how we can include women in this new economic thinking, Daniel agreed that Rawls didn’t say enough about gender, but suggested that his principle of fair equality of opportunity provides a comprehensive framework for gender equality, and that while there is more to do to tackle overt discrimination in education and the workplace, the main obstacle is the division of labour within the home, so we need to update legal frameworks on, for example, parental leave to challenge rather than reinforce traditional gender roles, while also improving conditions for people in part-time and flexible work. Anneliese argued that there is no proof that measures to help women would negatively impact male workers, and that while the gender pay gap was mostly driven by differences in occupation, the gap nowadays is also within occupations, while greater pay equality transparency tends to benefit all workers, and having more women in the workforce benefits male workers.

On a question about whether the division between left and right is less important than the divide between moderates and extremists, John agreed with Daniel’s earlier point that democracies have a credibility problem, but suggested that the divide is not just between moderates and extremists, because there are legitimate political debates about how to fix these underlying debates, and we haven’t solved enough of these problems over the last few decades. Ryan argued that populism is a left-wing as well as right-wing phenomenon, and that we can find a common ground between the left focusing on the impact of power dynamics on life outcomes and the right focusing on the impact of individual agency; Rawls talks about the role of brute luck in life alongside power and agency, and perhaps we can all agree that a lot in life is due to luck, so we need to build institutions to support people who suffer from bad luck but also provide everyone with opportunities to benefit from good luck.

NEXT EVENT

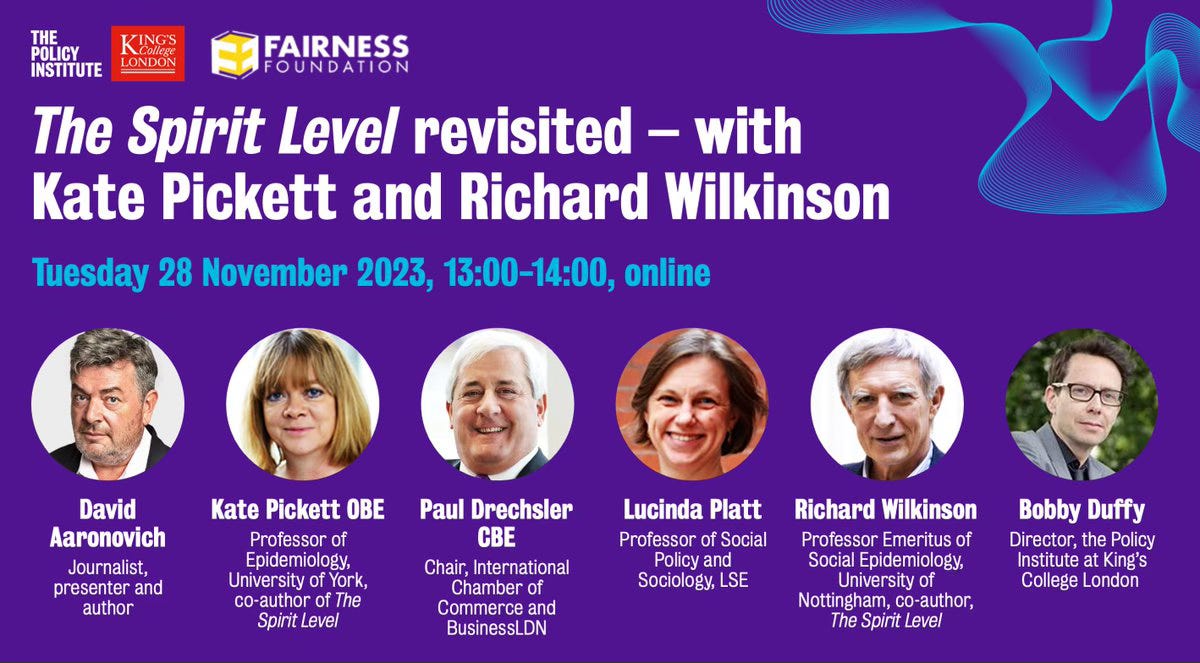

Our next event in this series is The Spirit Level revisited, with Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, on 28 November from 1pm to 2pm (UK time) on Zoom.

In their influential and award-winning 2009 book The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson argue societies with the biggest gaps between the rich and the rest are bad for everyone, including those who are most well off.

They contend that everything from life expectancy, mental illness and obesity to violence and illiteracy is affected not by the wealth of a society, but its level of equality and propose solutions to move towards a future that is both fairer and happier.

Join the Policy Institute and the Fairness Foundation for the next instalment of our Fair Society series, as we revisit The Spirit Level and its lasting impact on how we think about inequality.

Speakers:

Kate Pickett OBE, Professor of Epidemiology, University of York, and co-author of The Spirit Level

Richard Wilkinson, Professor Emeritus of Social Epidemiology, University of Nottingham, and co-author of The Spirit Level

Lucinda Platt, Professor of Social Policy and Sociology, LSE

Paul Drechsler CBE, Chair, International Chamber of Commerce and BusinessLDN and former President of the Confederation of British Industry

David Aaronovitch, Journalist, presenter and author

Will Snell, Chief Executive, Fairness Foundation (Chair)