Kleptocracy… and social mobility

How often do you get to read about kleptocracy and social mobility in the same newsletter?

Thanks for reading.

How often do you get to read about kleptocracy and social mobility in the same newsletter?

I was going to introduce some good news in this edition, but this doesn’t seem the right moment. Maybe next time.

Will Snell

Chief Executive

Fairness Foundation

PS: if you haven’t yet done so, please sign up to get Fair Comment in your inbox every Monday. Sign up for email updates

Russian kleptocracy

It has taken an outrageous and illegal act of war by Vladimir Putin to shake the government into any form of action in cracking down on dirty money, and it’s nowhere near enough.

The City of London has enabled and supported the kleptocracy that exists around Putin for decades. As Oliver Bullough argues: “We have been the Kremlin’s bankers, and provided its elite with the financial skills it lacks. Its kleptocracy could not exist without our assistance. The best time to do something about this was 30 years ago — but the second best time is right now.”

Nick Cohen suggests that the actions taken or promised in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will not go far enough. A key problem, in his view, is that our legal system is hardwired to privilege the interests of the wealthy: “There is institutional prejudice in the English justice system in favour of wealth that is as pervasive as institutional racism in the police.” A point picked up by Paul Lee in his recent blog post on unfair trials (which also looks at the Post Office Fujitsu Horizons scandal).

While we’re here, let’s not forget that unfair societies damage democracy and nurture autocrats and fascists, which is how we got here in the first place…

Social mobility — a chimera?

Our joint event last week with the Policy Institute at King’s College London (as part of the Fair Society series) focused on social mobility, and featured Professor Selina Todd talking about her book Snakes and Ladders: The Great British Social Mobility Myth.

🖥️ Watch the event or read a summary

Many would argue that the concept of social mobility is, at best, a distraction from tackling the larger problems caused by inequality, and at worst, ‘fake change’, the kind of call for progress that is acceptable to those who benefit from the status quo because it doesn’t threaten it in any way, and can be used to both justify and divert attention away from the underlying issues.

This line of argument does not claim that the efforts made in schools and elsewhere to help students from disadvantaged backgrounds to overcome the barriers that they face are anything short of heroic. But it does suggest that a society that applauds their efforts while normalising the underlying issues is an unfair society. It’s the same with food banks. Perhaps a fairer society would stop at nothing to tear down the barriers, rather than leaving the burden of compensating for them to the heroes of the frontline — teachers, volunteers at food banks and many others?

What we’re really looking at is two fundamentally different conceptions of society. In the first, inequality is fine as long as people can, in theory, pull themselves up the ladder and ‘escape’ from the bottom rungs. In the second, everyone can fulfil their potential and thrive, because the rungs of the ladder are less far apart.

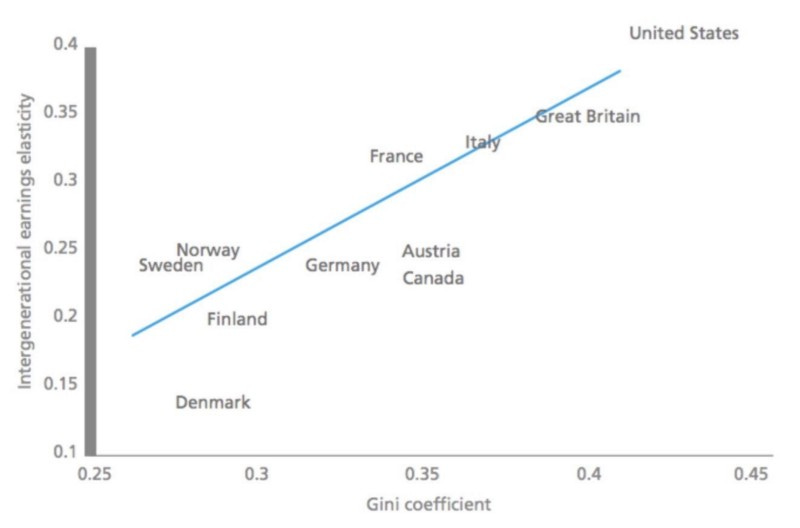

Chart of the week

Confession. This chart wasn’t produced this week. In fact, it is a decade old, and the concept (the ‘Great Gatsby curve’) is older still. But it illustrates a key point about social mobility, which is that it is difficult to point to opportunities to climb the ladder as a response to inequality. This is because there is a direct correlation between high levels of inequality (X axis) and lack of social mobility (Y axis). And the inverse is true. Simply put, the data suggests that you can’t have social mobility without greater equality.

Poll of the week

What’s the best way to make progress on social mobility?

What should we prioritise over the next decade: compensating for the barriers to opportunity that people face (e.g. by reducing the attainment gap in education), or removing those barriers (e.g. by reducing inequality more broadly)?

Last week’s poll focused on the role that luck plays in life, by asking you to rank the influence on life chances of various factors. Way out in front were circumstances at birth, followed by good or bad luck over the course of someone’s life, with talent and hard work bringing up the rear.

Reads of the week

Helena Gillespie has written for The Conversation about what the higher education funding shake-up means for students and universities, highlighting concerns about plans to limit loans for students who do not achieve certain grades, with reference to the disadvantage gap (and linked to the discussion above about social mobility).

Larissa Kennedy wrote in The Times (paywall) that the proposed university reforms are a heinous attack on opportunity, and that “far from levelling up, these classist, racist and ableist proposals will actively keep marginalised students down”. Experts agreed, with Ryan Shorthouse at centre-right think tank Bright Blue arguing that restricting access to student loans “penalises prospective students, disproportionately those from Britain’s poorest families.” However, Mary Curnock Cook took the opposite view, writing for the Higher Education Policy Institute that GCSE thresholds for eligibility for student loans could transform access and participation.

Also on tertiary education, Will Hutton argued in The Observer that “Britain needs to sustain its great university system and put training of the more than half the population for whom academic education does not work on the same footing, both in terms of financial access and in status”.

The cost of living crisis has not gone away, even if war in Ukraine has shoved it off the front pages. Annual forecasts by the housing charity Crisis and Heriot-Watt University, reported in The Guardian, predict that the number of people homeless in England is predicted to jump by a third by 2024, as councils warn of a “tidal wave” of need caused by benefits freezes, soaring food and energy bills and the end of Covid eviction bans.

Ian Mell and Meredith Whitten suggested in The Conversation that green space access is not equal in the UK — and the government isn’t doing enough to change that.

If you haven’t yet done so, please sign up to be emailed Fair Comment every Monday. Sign up for email updates

Please suggest anything we should include in (or change about) Fair Comment. Suggest content or changes

You can read all of the previous editions of Fair Comment on our website. Visit our Fair Comment page

Originally published at https://fairnessfoundation.com on February 28, 2022.