Nothing works any more

A discussion of the key arguments in Sam Freedman's recent book 'Failed State: Why Nothing Works and How We Fix It'

A new government is in power. Different people, different politics, different plans. But how much of a difference can they make to people’s lives if the institutions of the state are setting them up to fail?

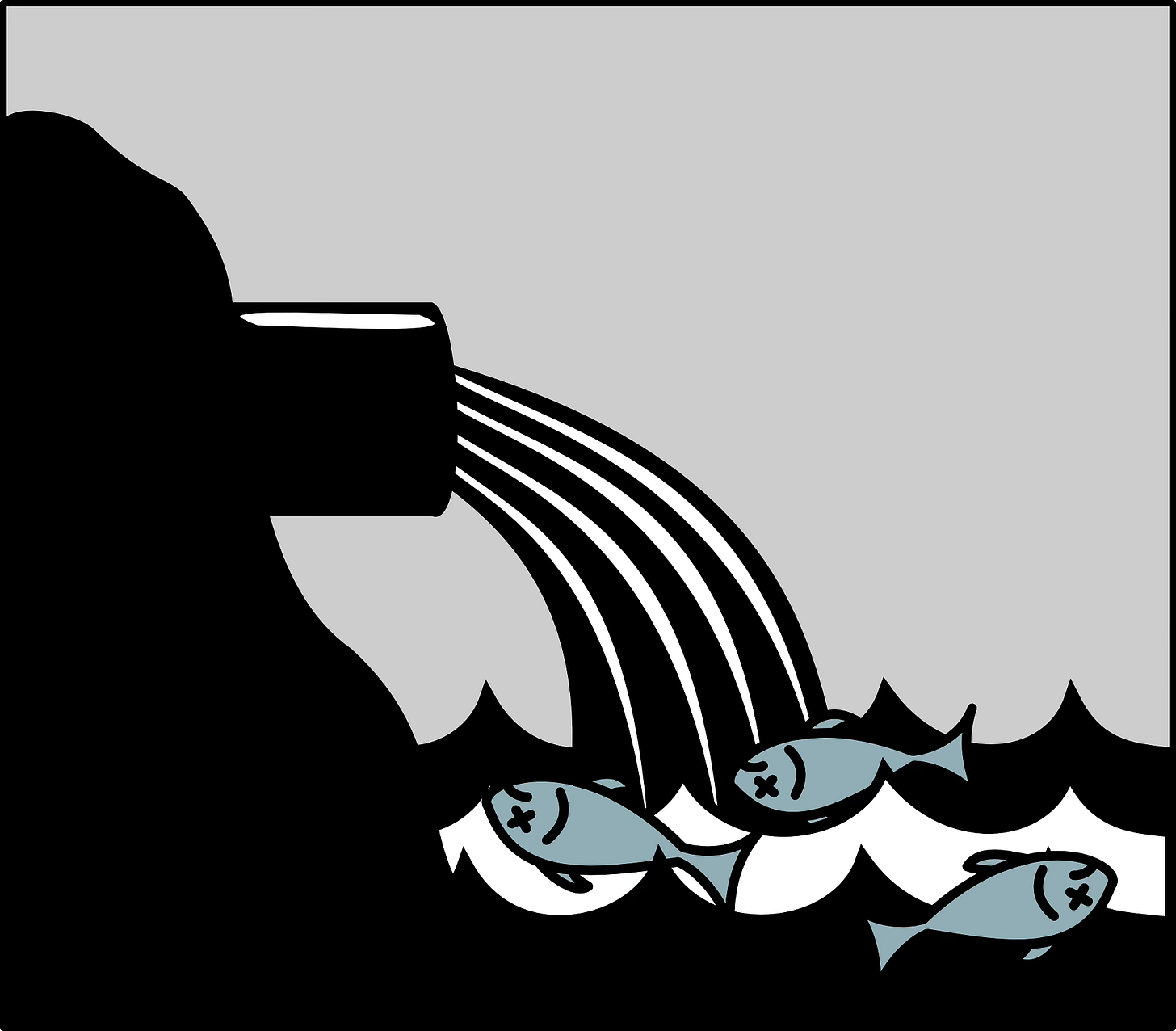

In his new book, Failed State, the political commentator Sam Freedman (author of Comment is Freed) outlines how it feels like nothing works in Britain anymore. It has become harder than ever to get a GP appointment. Many property crimes remain unsolved. Rivers are overrun with sewage. Wages are stagnant and the cost of housing is increasing. Why is everything going wrong? It's easy to blame dysfunctional politicians, but the reality is more complicated, Sam argues - politicians can make things better or worse, but all work within our state institutions, which are utterly broken.

Last week we and the Policy Institute at King’s College London hosted a webinar to discuss the book’s diagnosis and prescription for change, featuring Sam alongside Polly Curtis (Chief Executive of Demos), Emma Norris (Deputy Director of the Institute for Government) and Duncan Robinson (Political Editor and Bagehot columnist at The Economist), with Professor Bobby Duffy (Director of the Policy Institute) in the chair.

You can watch a recording of the hour-long event below, but underneath the video is a quick summary of the discussion, with some brief reflections from me.

Event summary

Sam outlined the three big trends from recent decades that he thinks have made it so hard to run the country:

Centralisation (to Whitehall, undermining the capacity and power of local government and then overwhelming central government to the extent that it has no capacity either to deal with big strategic issues or to deliver, and is reliant on poorly performing and unaccountable outsourcing companies; but also within Whitehall, with an overmighty Treasury filling the void of a weakened Number 10 post-Blair to the extent that spending controls are the only strategic driver of decision-making in government)

Scrutiny (the executive avoiding scrutiny from the legislature through tricks like timetabling changes in parliament and over-use of secondary legislation, leading to poor quality law-making, forcing both the Lords and the courts to become more involved in improving or challenging legislation; and less effective and robust internal scrutiny by the civil service in response to increased hostility to civil servants from government ministers)

Media (‘comms has eaten policy’ in reaction to the 24/7 news cycle and social media, such that politicians are incentivised to govern through constant policy announcements rather than developing effective long-term policies, while changing media consumption habits have reduced the money available to hire specialist policy correspondents, leading lobby journalists to report on policy issues as well as politics, but with a focus on the political aspects of policy, further incentivising the government to focus on meaningless announcements rather than effective policies)

Key issues raised in the panel discussion and audience Q&A:

There’s a broader problem of low trust and confidence of citizens in the state, which is self-perpetuating, because if politicians don’t feel trusted to make tough decisions, they will be inhibited and won’t act boldly to improve things

Devolution is messy and creates winners and losers (but arguably is better than the status quo, which mostly creates losers all round)

We’re stuck in a cycle of superficiality and short-termism, with lots of people in Whitehall and Westminster who are good in crises but less on long-term projects

Number 10 is too focused on the detail and not enough on strategic leadership

People in government matter as well as the systems, and we need to incentivise and support Ministers to make good, bold and often difficult long-term decisions

We need a better approach to evidence; Ministers talk the talk but really want policy-based evidence, not evidence-based policy, while civil servants sometimes stifle innovation because of a lack of ‘proper’ evidence

Solutions suggested by Sam and the panellists included:

Devolving more power (e.g. to mayors)

Having a more coherent (and limited) approach to outsourcing

Giving the legislative function of MPs more status and power

Making MPs more representative of the population

Involving citizens more in policymaking

Raising more money from taxes and spending more on local government

Giving Ministers more control (e.g. powers to appoint special advisors)

Focusing government on long-term missions to provide strategic clarity

Some reflections

In a 2023 post on his substack (The Policy Paradox), Sam identified three reasons why ‘no brainer’ policies (such as putting more money into preventative health) often never see the light of day. The first is Treasury spending rules - linking to the point in the book about the centralisation of government (the IFG also recently recommended reforming the centre of government to deliver more effectively on policy priorities). The second is misdiagnosis (wrong problem > wrong solution), which links to centralisation, scrutiny and the media. The third is ‘fear of the electorate’ - an often unjustified assumption that the public won’t like a particular policy.

In other words, not only is there a risk that, once in government, you pull a policy lever and nothing happens, but you’re also likely to be pulling the wrong lever, or you might not pull the lever in the first place, either because of fear of public (and media) reaction or because the iron grip of the Treasury won’t let you anywhere near the room with the levers in. (Of course, this leaves to one side the whole set of arguments that change also comes about through other means than governments pulling levers.)

In his book The Good Ancestor: A Radical Prescription for Long-Term Thinking, the philosopher Roman Krznaric identifies the barriers to long-term thinking (for the sake of argument, let’s equate this with effective policymaking, even if there’s not a perfect correlation), which echo some of the issues identified by Sam and his fellow panellists:

Human nature (“the inherent short-sightedness of our marshmallow brains”)

Outdated institutional designs (political systems geared to short time horizons)

The power of vested interests in an economic system “bent on short-term gains”

Insecurity in the here and now causing people to focus on immediate needs

Insufficient sense of crisis (boiling frog syndrome)

One of the key political issues that gets less attention than it deserves because of these barriers to effective policymaking is inequality. We argued in The Canaries and Deepening the Opportunity Mission that inequality is itself a barrier to the new government’s missions, and we’ll be publishing a ‘wealth gap risk register’ next month setting out how wealth inequality damages our society, economy, democracy and environment (and what we can do about it).

On the subject of inequality, our next event with the Policy Institute at King’s College London is tomorrow (Tuesday 17 September) at 1pm on Zoom, with Danny Dorling discussing his new book, Seven Children, with Dame Rachel De Souza (Children’s Commissioner for England), Georgia Banjo (Britain Correspondent at the Economist), and me. Find out more and sign up here.

Duncan Robinson is difficult to understand - can someone tell me what book he was referring to when he referred to another book he was reading at the same time as Sam's?