Rethinking the roots of poverty

A guest post from Barry Knight, co-chair of Compass

This article is written by Barry Knight, a social scientist and statistician. He is co-chair of Compass, adviser to the Global Fund for Community Foundations, and writes frequently for Rethinking Poverty. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect the views of the Fairness Foundation.

As we approach the general election on 4 July, I am struck by how little politicians are talking about the underlying structural problems of our society. Unless we address them, they will never go away, and the consequences are serious. Not only do chronic problems undermine our capacity to be a good society but, as they cluster together, they can cause the collapse of the systems that support our way of life. Our current crisis is a result of long-term neglect.

At the root of many of our problems, and one that we have never taken seriously enough, is poverty.

In 1909, at the launch of her Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905–09, Beatrice Webb claimed: “It is now possible to abolish destitution”. Yet, in 2022, more than 100 years later, Joseph Rowntree Foundation figures show that around 3.8 million people experienced destitution (where they could not afford to meet their most basic physical needs to stay warm, dry, clean and fed) in 2022. In all of our history, we have never managed to raise the incomes of the bottom quintile of society so that they can take full part in society.

Given the immense technological advances and economic growth since 1909, this can only indicate a failure of our social and economic policies. In 2017, I argued in my book Rethinking Poverty that we needed a new approach, so when Will Snell, Chief Executive of the Fairness Foundation, asked me for my thoughts on two questions to help frame a study by the Fairness Foundation, I readily agreed.

How much worse can we expect poverty in the UK to get?

My quick answer is ‘much worse’. This opinion is derived from multiple sources on the trends at work in our society. For example, an Observer editorial in March 2024 noted:

‘Poverty figures published last week show that in 2023 one in six British children lived in families suffering from food insecurity, up from one in eight children in 2022. And one in 40 children lived in a family that accessed a food bank in the previous 30 days, almost double the proportion the previous year. The growing number of children whose parents struggle to afford to feed them properly in a country as rich as the UK is a shameful reflection of just how low a political priority tackling child poverty has been for Conservative prime ministers and chancellors since 2010.’

The editorial continued:

‘Child poverty is rising on every official measure. Almost one in three children now live in relative poverty, defined as households with incomes of less than 60% of the median. And one in four children live in absolute poverty, in households with incomes of less than 60% of the median income in 2011. This represents the fastest rise in child poverty for almost 30 years. Almost half of children from black and minority ethnic backgrounds live in poverty, and 44% of children in lone parent families.’

JRF’s guide to understanding poverty, published around the same time, noted that:

‘Since last year’s report, we have seen even more evidence of the desperate measures that households are having to take to get by, and of the high tides of insecurity that have washed over more and more people.’

To probe this question more deeply, a useful heuristic is the ‘systems iceberg’. First developed by Edward T. Hall in 1976, this looks at how various elements within a system — which could be an ecosystem, an organisation, or something more dispersed such as a supply chain — influence one another. Rather than reacting to individual problems that arise, a systems thinker will investigate relationships to other activities within the system, look for patterns over time, and seek root causes.

The iceberg is a useful metaphor because it has only 10 percent of its total mass above the water while 90 percent is underwater. But that 90 percent is what the ocean currents act on, and what creates the iceberg’s behaviour at its tip. Global issues can be viewed in this same way.

The iceberg model typically has four categories. Above the waterline are ‘events’. Here is one such event, reported in the Newcastle Chronicle:

Newcastle Foodbank distributed over 337 tonnes of food in busiest 12-month period on record. The total number of food parcels issued between April 2023 and March 2024 was 25,570, an 8% increase on the previous year.

To put this single data point into perspective, we go to the next level down - ‘patterns and trends’. Here, we find that the figure from Newcastle Foodbank is not a blip, but is part of an exponential rise in the use of food banks over the past ten years. Taking data from the Trussell Trust website, I examined the number of emergency food parcels distributed by the Trust since 2017/18. The number of food parcels in each year is displayed in the following line chart.

The overall trend shows dramatic growth over seven data points. The regression line shows a strong upward trajectory - measured by the value of R2, which, at 0.90 on a scale between 0 and 1, is very high.

I have extended the trend forward beyond the data series by two years to estimate what happens by 2025/6. The answer suggests that the number of emergency food parcels will have more than doubled in the eight years from 2017/18.

To find out what is causing the trend, we go further down the iceberg to ‘structures and behaviours’. Here, we can identify the influence of austerity regimes that began in 2010 and the implementation of Universal Credit as factors likely to increase food bank use. This is due to what has been called the low-pay, no pay cycle, as people drift in and out of low paid work and experience cashflow difficulties as a result. A range of other factors have also put pressure on people and are driving up poverty. These include:

Benefit cuts. An article in the Big Issue projects that these will affect 450,000 disabled people, very few of whom will find work. A recent article in the Observer suggests that people with cancer, arthritis and amputations are among people being denied disability benefits.

Cost of living. The Office of Budget Responsibility reported in March 2024 that inflation is still running at twice its target level, benefits are taking time to catch up with rising prices, employment is starting to fall, earnings are still below their 2008 levels, and housing costs are increasing rapidly. Given that average household disposable incomes will continue to fall until 2024/25, these effects will have a profound impact on many people’s living standards for years to come. According to the New Economics Foundation, the cost-of-living crisis is hitting hardest in those areas that are supposed to be being levelled up.

The failure of levelling up. There is a wealth of evidence that the 2019 commitment to ‘level up’ certain areas has not worked. It was ‘stymied from the very start’, was full of broken promises and has let local people down, and condemned as arbitrary by local authorities.

Cuts. Many local authorities are effectively bankrupt and people pay a lot more to receive a lot less. The result is a litany of cuts: cancelled road projects, hacked-down adult social care and transport for children with special needs, drastically altered bin collections and, to cap it all, huge increases in council tax.

Loss of hope. According to some, the biggest failure is the despair it has created about Britain’s future. Evidence for this can be found in the huge increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders among children.

Below the structures and trends, we find mental models and worldviews. At this level, we find widespread hostility towards people in receipt of social security payments and a view that people in poverty have made bad choices, meaning that the state should not look after them.

This is part of a worldview that gives primacy to the market as the arbiter of human value. In a recent article, George Monbiot has pointed out that the market:

‘...will, if left to its own devices, determine who deserves to succeed and who does not. Everything that impedes the creation of this “natural order” of winners and losers – tax and the redistribution of wealth, welfare and public housing, publicly run and funded services, regulation, trade unions, protest, the power of politics itself – should, albeit often subtly and gradually, be shoved aside. It has dominated life in this country, to a degree unparalleled in similar nations, for 45 years.’

Given that the signs of market failure are all around us, it is perplexing that so many in politics still see it as the solution to all of society’s problems. Andy Becket asks: Margaret Thatcher set Britain’s decline in motion – so why can’t politics exorcise her ghost? He notes:

‘From the crisis at Thames Water, a company created by her naively pro-monopoly privatisation programme, to the precarity and spiralling cost of renting a home – both products of her curtailment of tenants’ rights and council housing – her policies’ flaws, limits and unforeseen consequences are ever more apparent. Less directly but just as damagingly, her hostility to the EU, to taxing the rich properly, and to most state services except the military, set this country on a path towards today’s European isolation and public and private poverty.’

Going still deeper into mental models, we unearth the widely accepted definition of economics. This is the classic definition given by Lionel Robbins in 1932 in which he says:

‘Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.

(Robbins 1932, p. 15)

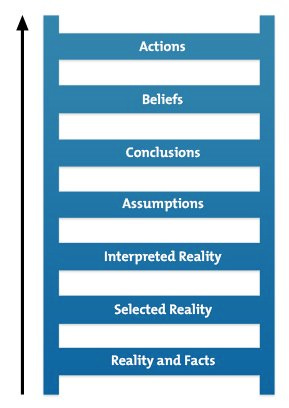

What lies at the root of our problems is the idea of scarcity. In Robbins’ formulation this lies at the bottom of the systems iceberg, and is of critical importance to what happens in the system. This is because of what cognitive scientists call the ladder of inference in the way that mental models affect the way that we take decisions about action in the world.

Scarcity implies competition for resources and therefore implies winners and losers. The elimination of poverty requires that we develop a philosophy of flourishing lives for all – not the division of the world into winners and losers. There is therefore a deep flaw in the way we interpret our society that is expressed in the necessity of poverty. For as long as we think in binary categories we will always have ‘them’ and ‘us’, and poverty will always be with us.

As we noted earlier, there has never been a time in the 80 years since the Second World War when the bottom quintile of our society was not excluded from the fruits of economic growth. However, as we approach a general election on 4 July, both Labour and the Conservatives emphasise economic growth, but without demonstrating how this would translate into wellbeing for the mass of everyday people who are presently struggling with high prices, low wage rates, benefit cuts, poor housing, failing social and health services, climate change and a sense that our public infrastructure is at breaking point. It has been known for more than 30 years that the neoliberal model of economic growth benefits the top end of the income distribution and tends to impoverish the bottom 40 per cent.

So, the conclusion is that poverty has risen dramatically in recent times and will almost certainly continue to do so. According to the Financial Times, if we leave out London, poverty in the UK is now on a par with Mississippi, America’s poorest state, and the capital “...is the one thing keeping the UK hanging on in the upper economic echelons”.

What to do about it

The first step would be to acknowledge that our approach to poverty has not worked. This is not simply a question of recent statistics going in the wrong direction, but a long-term failure of state governance. My proposition is that we need to abandon the idea that ‘the gentleman in Whitehall knows best.’ This top-down philosophy has driven the organisation of British society since the end of the Second World War and has resulted in a sense of powerlessness throughout society. A ferment of ideas emerges from people whose voices are rarely heard by our political elites.

Listening to people would inevitably result in reframing the purpose of our society, so that it emphasises human flourishing for all, rather than economic development for a few. In pursuing this goal, we would see human beings as part of and equal to nature so that we pursue ‘a different kind of growth’. Drawing inspiration from Sue Goss’s thesis that we must replace ‘machine mind’ with ‘garden mind’, we take our cue from nature. We must learn from the Garden Cities movement, which puts the economy in the service of the idea of human flourishing in a beautiful environment, rather than treating people as a factor of production in service of a machine-based economy. We would support the ‘Right to Grow’ campaign, which puts good food, local agency and participative ways of doing and deciding at the heart of our endeavours.

It follows that we pursue beauty, both natural and artistic, so that when we build, we build as if we are building forever. In the process, we nurture our inner consciousness in favour of a sense of joy in all we feel and do. This requires that we face and incorporate our shadow-self that keeps us shackled to fear-based feelings and actions that damage ourselves and those around us. We must develop formal arrangements of governance that enable our creative imaginations and sense of power and agency to pursue our energies in favour of flourishing lives for ourselves and others who share our world. This yields three key understandings of our future priorities:

Flourishing lives depend entirely on the restoration of nature and the long-term sustainability of the planet.

Flourishing lives depend on meaningful and vibrant democracy. This requires a shift of power between the state and the citizen so that the local community has the power to shape the decisions which directly impact on their future. This in turn implies a new role for the national and local state in nurturing and enabling community activity, as well as robust individual citizens’ rights to protect the interests of minorities and minimum legal safeguards to ensure that the results of decision-making support human thriving.

Achieving flourishing lives requires an evolution of our economy so that the foundations of a good life, including everything from housing to energy to childcare, are organised not to extract but to share wealth more effectively, such that the economy meets the basic needs of everyone in a more equal way. To achieve this, the organisation of these foundational parts of our economy needs to be based on a mutualised approach.

Evidence to date suggests that the Labour Party has no interest in the deep questioning of the purposes of governance in ways that would transform society in the way suggested above. Labour is committed to economic growth. In the Mais Lecture, Rachel Reeves, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, recognised:

‘...the priority of ending stagnation. This, Reeves argues, demands a new model of economic management guided by three imperatives: stability; “stimulating investment through partnership with business”; and reforms that will unlock productivity. Her big theme here, one on which we should agree, is that without widely shared growth, democracy itself could be in peril.’

In the same lecture, she highlighted the importance of following the fiscal rules, which means that there can be little increase in expenditure on factors that would reduce poverty (such as the two-child limit on benefit payments).

It appears that the issue of poverty has not the same salience in political circles as it did 20 years ago. In 2021, when she was Shadow Education Secretary and Labour child poverty spokesperson, Kate Green spoke at the launch of the second edition of Ruth Lister’s book Poverty. She expressed regret that “rich, informed discussion of poverty has disappeared from political discourse”. She said that the issues around poverty “were more widely understood 20 years ago among the ‘political classes’”.

The relative lack of interest in poverty has been a feature for many years, and it is hard to see what would turn this around. This is breeding a sense of fatalism in civil society. Leading community activist Imandeep Kaur, for example, tweeted on 12 May 2024:

‘I fundamentally think it’s too late for a lot of the eco modernist ideas being proposed they can emerge out of collapse, in a softer way, but not as a transition from extractive capitalism, and I think they are now a huge distraction and we all going to suffer BIG TIME.’

It seems to me that it is important that civil society does not succumb to despair and to recognise the point made by Andrew Rawnsley, political editor of the Observer: Don’t despair. History shows Labour even cash-strapped governments can be radical. Rather than moaning about the situation, a better approach is one taken by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which is to build an infrastructure for change:

‘JRF has a proud history of building elements of insight infrastructure which have become essential parts of social policymaking in the UK – from the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) which underpins the Real Living Wage, to our essential guides to the scale and nature of poverty and destitution in the UK. We will continue to build on these anchor studies with new elements of insight infrastructure. In addition, we are building new infrastructure to support other elements we believe are essential to social change – including imagination, storytelling and movement building.’

We can learn from citizens’ movements that build power and influence politics. Tyne and Wear Citizens, for example, has transformed Newcastle into a ‘living wage city’.

We need a new vision. A first step would be to go back to Beveridge and understand what he actually said, rather than what people think he said. In 2012, I contributed to a Fabian Pamphlet called ‘Beveridge at 70’. In it, I pointed out that Beveridge hated the term ‘welfare state’. His vision gave primacy to the role of mutual aid in the delivery of services. He feared the ‘cold bureaucracies’ that would dehumanise us. A more appropriate description of what he wanted would be a ‘welfare society’. He stressed the importance of people taking control of their lives – a dimension that was almost entirely lacking in the implementation of his report.

If we want to end poverty, we cannot wait for governments to solve this problem for us; we have to find the solutions ourselves and press governments to do what we want. In this, we can learn from the #ShiftThePower movement that has taken root in the Global South.

We are actively pursuing this perspective in the next stage of our work. If you are interested in this, please be in touch with me at barryknight@cranehouse.uk.

Barry Knight is a social scientist and statistician. He is co-chair of Compass, adviser to the Global Fund for Community Foundations, and writes frequently for Rethinking Poverty. He has worked with and advised funders such as the Ford Foundation, the CS Mott Foundation, the Webb Memorial Trust, the Arab Reform Initiative, the H & S Davidson Trust, and the European Foundation Centre (now Philea). He is a management team member of Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace and works with Foundations for Peace. Barry has held appointments at Cambridge University and in the British Government. Barry is the author or editor of 15 books on poverty, civil society, community development and democracy, including Rethinking Poverty: What makes a good society?. He has published more than 100 articles on topics as diverse as economic development, crime and delinquency, family policy, children’s services, voluntary action, civil society and philanthropy.