Unequal wellbeing makes for a sick society

A landmark report by Carnegie UK shows alarming gaps in wellbeing between different groups in society; the implications are stark

Carnegie UK, in partnership with Ipsos, have today published their Life in the UK Index, which measures the wellbeing of people in the UK through a survey of over 6,900 people that asked questions across four themes: social, environmental, economic, and democratic.

This huge and ambitious research project finds that, while overall wellbeing for people in the UK in 2023 is 62 out of 100, this ‘could do better’ score masks concerning gaps in wellbeing across different groups.

Their key findings:

People who have a disability, live in more deprived areas, have lower annual household incomes or live in social housing or private rented accommodation experience lower collective wellbeing.

Democratic wellbeing is exceptionally low, indicating a crisis in trust in institutions across the UK.

Older people have some of the highest levels of wellbeing while younger people experience multiple challenges to their wellbeing.

Coming ahead of Friday’s publication of the latest quarterly update of the recently updated ONS UK Measures of National Well-being Dashboard, the report makes three recommendations:

Governments must act to reduce wellbeing gaps between socio-economic groups

The UK government must legislate to protect the wellbeing of future and current generations and to include wellbeing outcomes and indicators in policymaking

Political parties and governments must act urgently to strengthen democracy

The disparities between the collective wellbeing of different groups (summarised in the report screenshot below) are striking, but there are even greater inequalities when we look at scores for specific areas of wellbeing. For example, there is a 23-point gap between the economic wellbeing score of social housing tenants (52) and of homeowners (75). And there will of course be intersectional dynamics at play that lead to yet more stark differences for people affected by multiple forms of disadvantage.

The differences between generations have yielded the most media interest so far. Solutions are needed urgently to the problems of intergenerational unfairness, and should be guided by the wealth of existing research on public attitudes in this area, including Bobby Duffy’s work and Jane Green’s research with colleagues at the Nuffield Politics Research Centre.

Another striking finding is that, while there is a linear relationship between annual household income and economic wellbeing for incomes up to £100,000, levels of wellbeing plateau above this point.

And we know that low levels of wellbeing for some groups in society affect us all, in multiple ways. IPPR’s Commission on Health and Prosperity recently showed that poor physical health undermines productivity and economic growth, while there is evidence that poor mental health costs the economy billions every year.

These relationships were famously explored by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson in their influential and award-winning 2009 book The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, where they argued that societies with the biggest gaps between the rich and the rest are bad for everyone, including those who are most well off.

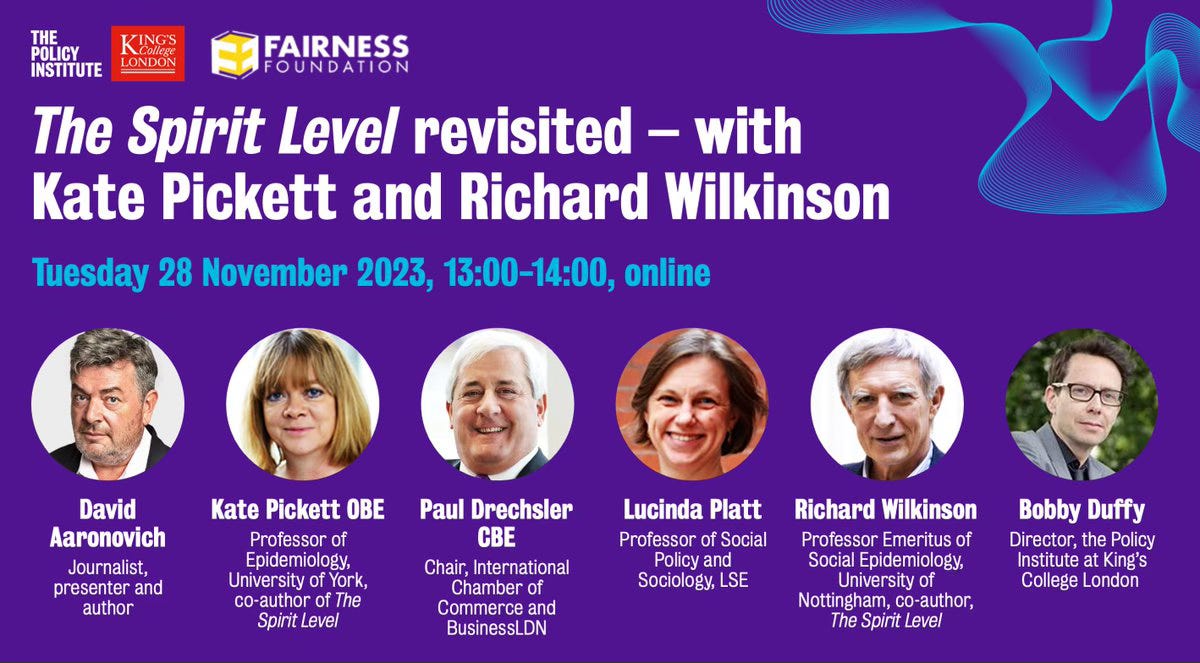

Our next event with the Policy Institute at King’s College London is The Spirit Level revisited, with Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, on 28 November at 1pm on Zoom.