Who are the 15% who aren't bothered about inequality?

Our polling finds a fairly consistent 15% who are unconcerned about inequality and oppose action to tackle it. Who are these people, and are they always the same people or do they vary by issue?

In polling that we have carried out over the last couple of years, we’ve found a striking level of consistency in the proportion of respondents who are either unconcerned about inequality or opposed to policy solutions aimed to address inequalities. With a few exceptions, about 15% of the British population fall into this group. For example, in our polling on attitudes to inequality with Ipsos (Fairly United) in 2023, 15% of Britons thought that inequality was not an important problem.

We decided to commission some quick analysis of a subset of our recent polling to explore who these people are, whether they are the same group across every issue, and whether they share any demographic characteristics beyond political affiliation. With limited time and budget, we decided against a detailed investigation using machine learning techniques, and instead commissioned the excellent data analyst Susie Mullen to look at the results of three of our recent polls, with a focus on five answers across those three polls:

In our polling on attitudes to inequality with Opinium (Unequal Kingdom) in 2024, 14% said that inequalities between people of different genders is not a problem at all, while 15% said that inequality helps people to fulfil their potential

In our polling on attitudes to tax reforms with Opinium (Minority Sport) in 2024, 16% said that the government should reduce taxes and spend less on public services, while 15% said that income from wealth should be taxed at a lower rate than income from work

In our polling on attitudes to luck with Opinium (Rotten Luck) in 2024, 14% said that educational attainment is completely down to merit, with no link to luck (i.e. circumstances outside people’s control, such as family wealth)

Susie looked at the demographics of the participants who belonged to the ‘unbothered’ 15% across all three studies. She compared their demographic characteristics against the rest of the participants for each study (all of which were based on nationally representative samples of around 2,000 people across the UK), to help us to work out whether there is a consistent group of people who oppose action on inequality, or whether the make-up of this group varies based on the issue at hand.

Below is a summary of Susie’s findings. If you’re not into statistics, feel free to skip to the conclusions at the end!

Overlaps between groups

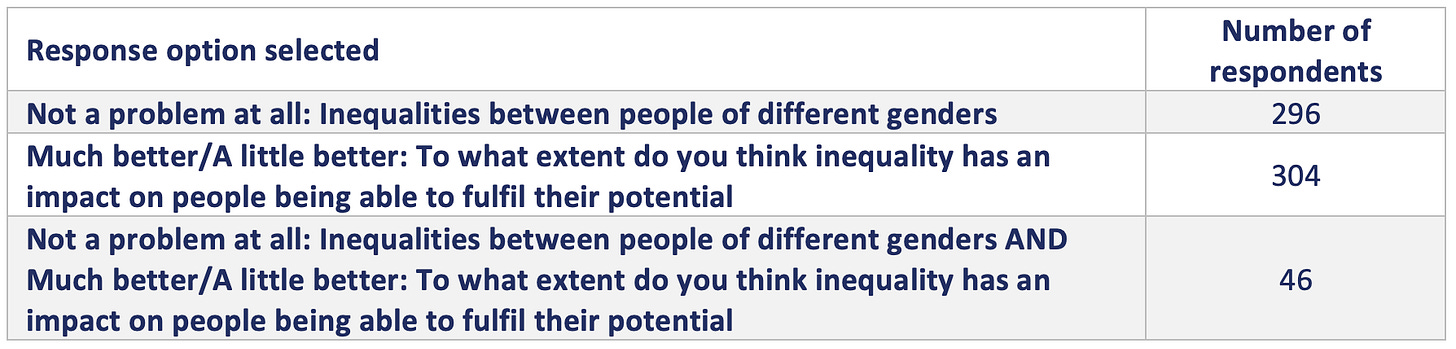

Where possible (when there was more than one group in the study), we looked at whether the same people were in each ‘15%’ group. We found that the proportion of people in each polling population that fell into the same ‘15%’ group was small.

In Minority Sport, only 95 out of 2,134 respondents said both that the government should reduce taxes and spend less on public services, and that income from wealth should be taxed at a lower rate than income from work. This equates to around 30% of the total who selected each option.

In Unequal Kingdom, an even smaller number of respondents selected both ‘15%’ options: 46 out of 2,050 respondents said both that inequality between people of different genders is not a problem at all and that inequality helps people to fulfil their potential. This equates to around 15% of the total who selected each option.

When reviewing the subsequent results it is important to consider that, in the instances we could test, the groups are discrete, with little overlap between respondents.

Demographic similarities

We did find some limited demographic similarities amongst groups who are less concerned about inequalities, and less supportive of action to tackle it.

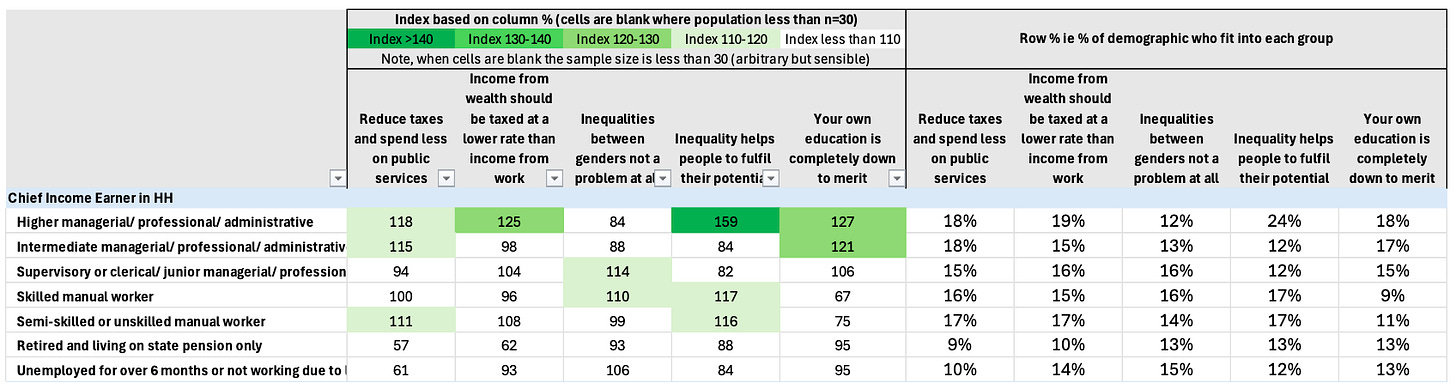

Gender, age, education level and socio-economic background

People in the ‘15%’ tend to be male; men are over-represented (compared to the sample) in all ‘15%’ groups except ‘education being down to merit’.

It is not clear from the data that a specific age group of men are more likely to be in the ‘15%’, and it seems that age is a factor that relates more to the question being asked than to the group itself. This is illustrated in the table below, where younger men (under 34) are not in the same groups as older men (over 45).

While age does appear to relate to the question being asked, students are over-represented in three of the five groups: ‘reduce taxes and spend less on services’; ‘tax income from wealth at a lower rate then income from work’; and ‘education being down to merit’.

However, there is no relationship between the groups and level of education.

People in higher managerial professional jobs are over-represented in four out of five ‘15%’ groups, with an average of 20% of people with these jobs falling into one of these groups. The only group in which they are not over-represented is ‘inequalities between genders is not a problem’.

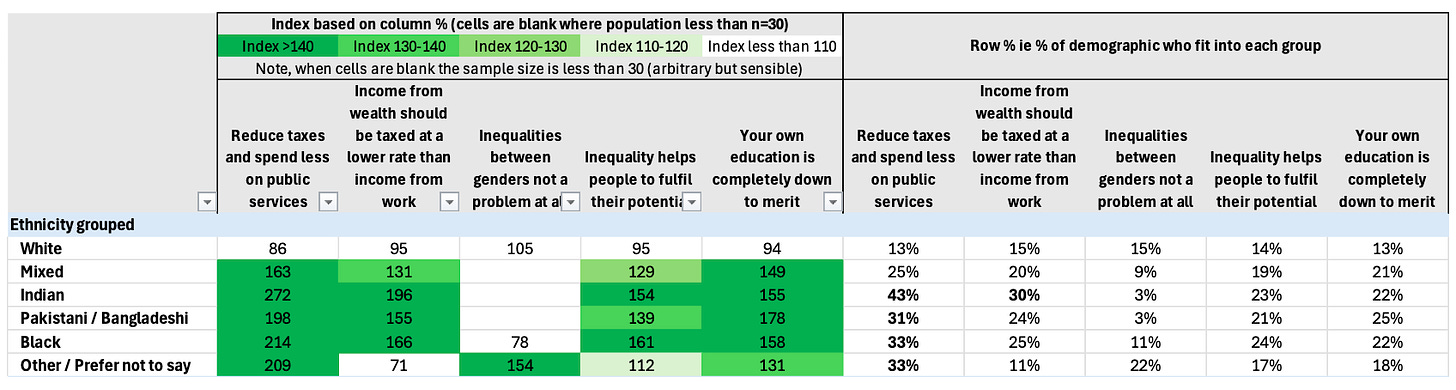

Ethnicity

Respondents who are not White are over-represented in all ‘15%’ groups except ‘inequalities between genders not a problem at all’. 29% of Indian respondents, 25% of Pakistani/Bangladeshi respondents and 26% of Black respondents are in one of the other four ‘15%’ groups, compared with an average of 14% of White respondents.

Politics

Conservative voters (both 2019 general election and voting intention in 2023/24) are over-represented in all five of the ‘15%’ groups. On average 20% of those who said they intended to vote Conservative fall into the ‘15%’, compared with 19% who voted Conservative in 2019.

Conclusions

When we look at the characteristics of people who are not concerned about certain forms of inequality (because they do not see them as being unfair) or are not supportive of certain measures to tackle inequality, it is not possible to identify any concrete patterns in terms of who those people are. While they are more likely than the average person in the UK to have certain characteristics (male, professional, Conservative-voting, ethnic minority background), these differences are not significant: there was not a single case when more than half of any given demographic group fell into the ‘15%’ group for any of the questions analysed.

There is also fairly limited cross-over in these groups across the five questions analysed. In other words, we are not looking at a single identifiable sub-section of the British population who are broadly opposed to action on a range of types of inequality. In fact, the demographic characteristics of people who are opposed to action on specific inequalities varies quite considerably.

This suggests that the composition of the ‘15%’ of people who are less concerned about inequalities, and less supportive of action to tackle inequalities, is driven more by the ‘what’, the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ than by the ‘who’ - by the question being asked, and by the worldviews, beliefs, attitudes and life experiences of the respondent, more than by demographic factors such as gender, ethnicity, education or home ownership.

Of course, segmenting the British population by their values, beliefs and attitudes is common practice, with More in Common’s seven segments a good example of how this can be applied in a political and policy context. And people like Ben Ansell and Steve Akehurst have done lots of research into how factors like education and home ownership do have a bearing on attitudes and beliefs. But perhaps the overall conclusion to be drawn from a quick look at the ‘15%’ is that they aren’t a single group of people who can be neatly defined or isolated. Our arguments need to reach and persuade as many people as possible, all of the time.

The wording in the questions you asked are the typical wording you find in the Conservative Party mind set and the right-wing MSM.

The People who are against actions for equality in society are mist likely the ones who are not affected by it.

You should turn your result around. Instead of highlighting and thus excusing/encouraging the 15% who are against actions on inequality you should say 85% of the population IS for action on inequality!!