Who is entitled to fairness?

Politicians often suggest that some groups in society are nearer the front of the fairness queue than others. What are we to make of this?

Our conception of fairness evolved thousands of years ago. To quote The Fair Necessities:

“Evolution through natural selection favours animals that look after their own self-interest, but humans flourished by building large social groups that depend on co-operation, which is sustained by fairness: equalising rewards across a group, sharing resources fairly and punishing selfish behaviour. This is cross-cultural, and children can understand it before they can talk. We are the only species that routinely chooses to help others and reacts strongly to perceived injustice. We have strong instincts for procedural fairness and for reciprocity, but also for ensuring that everyone has their basic needs met and has a fair chance to succeed. Societies that do not uphold this inbuilt sense of fairness become more divided and turbulent, and less successful.”

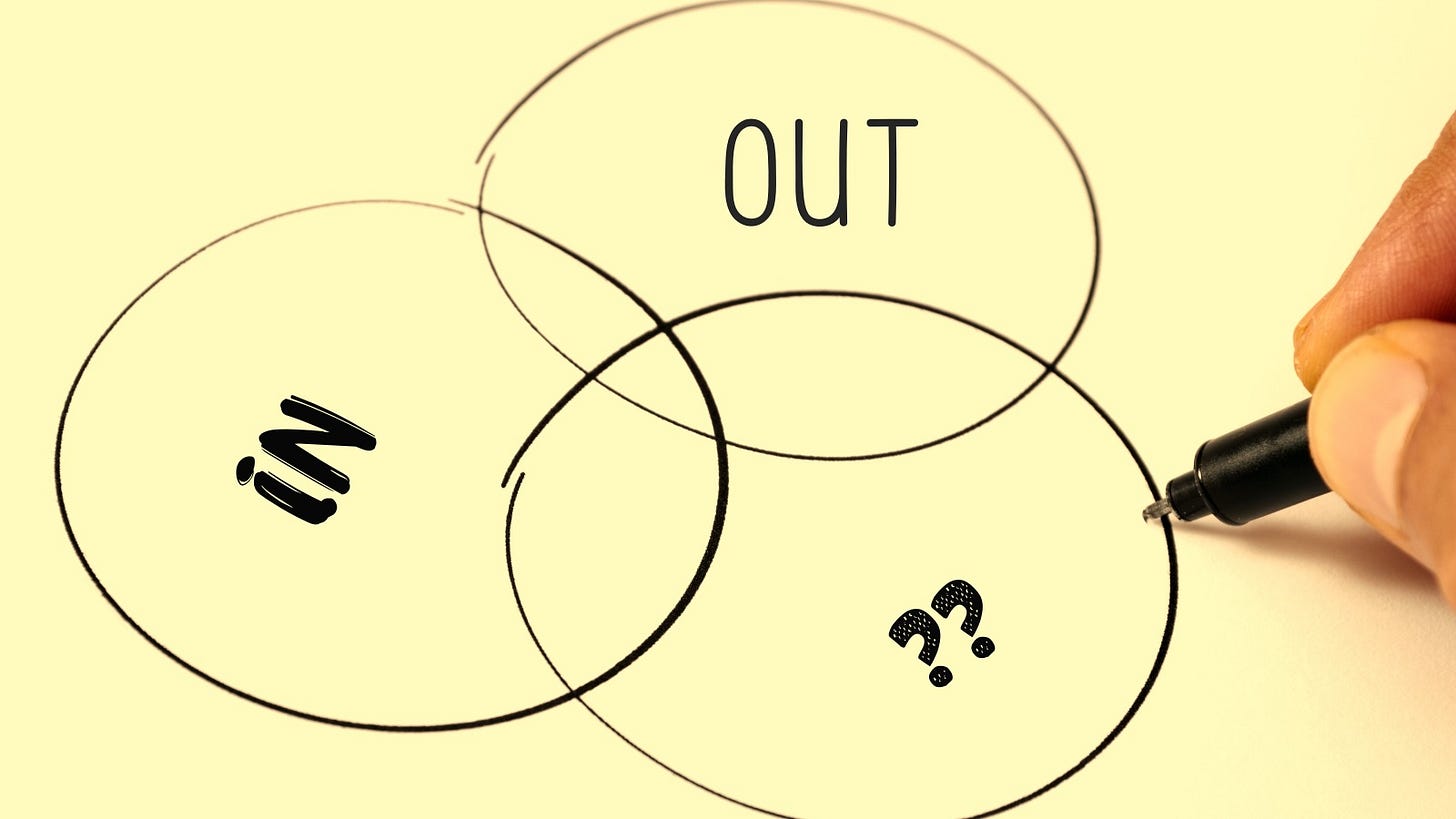

Even back then, it wasn’t always easy to decide to whom fairness applied, however. People generally thought about fairness, and put it into practice, in relation to their social group. By definition, therefore, some people were outside that group, and were not necessarily entitled to fairness.

Fast forward to today, and debates about fairness are arguably as often about which ‘insiders’ are entitled to fairness, and which ‘outsiders’ are not, as about the core principles of fairness itself (such as trade-offs between fair process and fair outcomes).

In recent decades, a lot of effort has been expended on whipping up public outrage against some groups of outsiders, in particular people on benefits and people migrating to the UK. However, as Sam Freedman pointed out earlier this year and as recent research findings by the British Social Attitudes survey and the World Values Survey have confirmed, fewer and fewer Brits these days believe that most or even some of society’s ills can be blamed on either group.

Nonetheless, politicians often talk about fairness in relation to one group in particular, with the implicit or explicit understanding that other groups should not expect to benefit from it, or at least are second in the queue.

Look at Jeremy Hunt’s speech to the Conservative conference a week ago, for example:

“I’m proud to live in a country where, as Churchill said, there’s a ladder everyone can climb but also a safety net below which no one falls. That safety net is paid from tax. And that social contract depends on fairness to those in work alongside compassion to those who are not.”

There’s a tension here between fair process and fair outcomes, to be sure. But at a deeper level there’s an ambiguity about whether people out of work are entitled to fairness at all - or whether they only qualify for second-tier principles such as compassion or charity. Hunt is more nuanced about this than some of his predecessors as Chancellor; George Osborne sometimes justified austerity on the grounds of fairness for taxpayers, explicitly casting the four in ten Britons who don’t pay income tax as undeserving of fairness, despite his repeated insistence that “we’re all in it together”. He said in 2012:

“…it's unfair that when that person leaves their home early in the morning, they pull the door behind them, they're going off to do their job, they're looking at their next-door neighbour, the blinds are down, and that family is living a life on benefits. That is unfair as well, and we are going to tackle that as part of tackling this country's economic problems.”

The shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has just made her speech to the Labour conference. Her references to ‘hope and security’ seem at first glance to apply to a broader group:

“Labour’s task is to restore hope to our politics. The hope that lets us face the future with confidence, with a new era of economic security because there is no hope without security. You cannot dream big if you cannot sleep in peace at night. The peace that comes from knowing you have enough to put aside for a rainy day and the knowledge that, when you need them, strong public services will be there for you and your family.”

But is she talking about delivering hope and security for everyone? Her speech was also peppered with references to ‘working people’, but it is (perhaps deliberately) ambiguous who the implied ‘out’ group is here. Is it people who are too wealthy to need to work? Or people who either can’t find work or are unable to work?

We’ve been researching how politicians in the UK have talked about fairness over the last 25 years in parliament, including how they talk about who is - and isn’t - entitled to fairness, and why. We’ll be publishing our findings in the coming weeks, so keep an eye out.

EVENTS UPDATE

How to create a fair society: can the left and right find common ground?

Webinar: Thursday 26 October 2023, 13:00–14:00 BST

How do politicians from the Conservative and Labour parties think about what a fair society looks like? Are their differences intractable, or are there areas with as-yet unrealised potential for cross-party consensus? If we can find common ground between the fairness principles and priorities of those on the left and the right, what might this look like in terms of concrete policy solutions? In his new book, Free and Equal: What Would a Fair Society Look Like?, Daniel Chandler builds on the philosophy of John Rawls to argue for a society that protects free speech and transcends culture wars, limits the influence of money on politics, and builds a more just economy that operates within the limits of the planet.

Speakers:

Daniel Chandler, economist and philosopher, author of Free and Equal

Anneliese Dodds MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Women and Equalities, Chair, Labour Party

John Penrose MP, Chair, APPG for Inclusive Growth

Ryan Shorthouse, Executive Chair, Bright Blue

Suzanne Hall, Director of Engagement, Policy Institute at King’s College London (chair)

Mark Carney on Value(s)

In the latest in our series of online Fair Society events with the Policy Institute at King’s College London, Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England, talked about his recent book Value(s): Building a Better World for All with Nick Macpherson, former Permanent Secretary to the Treasury and Policy Institute Visiting Professor with the Strand Group. You can watch the recording below or on our event webpage.

Towards the Manifestos

You can watch our Conservative Party conference event last Tuesday, in partnership with the Policy Institute, below or on our event webpage. The event focused on the Conservative agenda on poverty and inequalities and featured John Penrose MP, Professor Bobby Duffy, Julia Davies of the Patriotic Millionaires, and Sophia Worringer at the Centre for Social Justice.

The next event in the series takes place tomorrow at Labour Party conference (you can just turn up if you have a conference pass):