Why Britain’s outdated tax system needs to shift from earnings to capital

A guest post from Stewart Lansley, visiting fellow at the University of Bristol

This guest post is written by Stewart Lansley, a visiting fellow at the University of Bristol, a Council member of the Progressive Economy Forum, and the author of The Richer, The Poorer: How Britain Enriched the Few and Failed the Poor, a 200 year history.

There’s no question that Britain’s tax system needs a fundamental overhaul. In contrast with the progressive model of the post-war era based on ability to pay, taxes today bear as heavily on low and middle income groups as on the richest. Total tax revenue may be close to an historic high. But restrained by a broadly flat tax system and widespread avoidance by the wealthy, the sum raised is woefully inadequate to fund decent public services. It is no coincidence that the total tax take has rarely crept much above 35/36%, below the typical level achieved in other comparable countries.

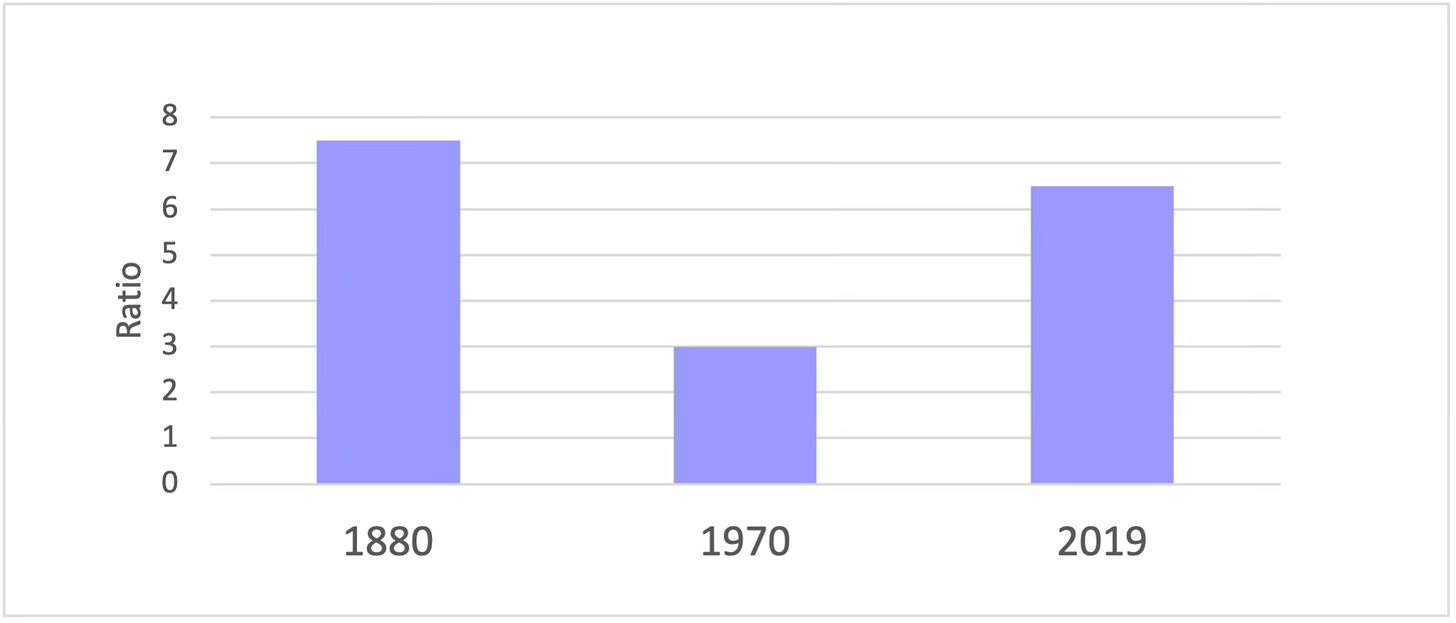

One of the most fundamental flaws is the bias to taxes on income from work rather than from assets (on dividends, capital gains and inheritance). While income is taxed at an average of around 33%, wealth is taxed at less than 4 per cent. Yet despite its dismal economic performance since the millennium, Britain is increasingly asset rich. As chart 1 shows, private wealth holdings are worth close to seven times the size of the economy, up from three times in the 1970s. Moreover, most of this great surge in wealth has been captured by the already rich. It also has little to do with a leap forward in wealth creation that would have served the common good. Most of it has been unearned, the product of endemic corporate wealth extraction, the rolling sale of former public assets, and state-induced asset inflation.

Improving economic performance and boosting social resilience requires a modest and phased tax shift from income to capital. High levels of tax on earnings distort choices about work and enterprise and weaken the state's ability to generate sufficient tax revenues. Through political inertia, the tax system has become badly skewed. It has failed to catch up with the growing importance of wealth over income in the way the economy operates, and does little to dent the growing concentration of wealth holdings at the top. The inequality gap is at its starkest when it comes to wealth. The Gini coefficient, a summary measure of the gap, is 0.36 for income compared with 0.6 for wealth.

While wealth offers security to households, those who need it most are the least likely to be able to fall back on private assets. When asked in surveys what they own, many people say ‘their mobile phone’. Indeed, the share of all wealth held by the poorest half of the population has never exceeded a tenth, and has actually fallen since the 1970s. Even a modest shift towards capital taxation would help to build a more progressive overall tax system.

The fall-out from the low taxation on wealth is well illustrated by the role of inheritance. An accident of birth, this remains the dominant source of both aggregate wealth holdings and a household’s rank in wealth levels across society. Its significance has also risen sharply in recent decades. Those born in the 1980s are likely to receive more than twice the sum relative to their income compared with those born twenty years earlier. Inheritance is the key source of the reproduction of the privileges of the past and, despite repeated government promises, it plays a big role in Britain’s persistent failure to tackle the great and growing gap in life chances. Moreover, the scale of the transfer from the so-called 'baby boomer' generation to the young is set to dwarf all previous wealth transfers, and drive even higher levels of wealth inequality.

Assets tied up in wealth pools are often little more than passive resources, while big inter-generational wealth transfers can play a counter-productive role in the economy, even more so when they are lightly taxed. Around 36% of all wealth is stored in property and mostly only realised when passed on through inheritance and gifts, where its benefits are enjoyed by the already privileged, and often spent on property. Little of this process contributes to more productive activity, with one of its primary and malign effects being to fuel higher house prices.

These fault lines have long been recognised. “A power to dispose of estates forever is manifestly absurd”, declared the patron saint of economics, Adam Smith, 250 years ago. “The earth and the fulness of it belongs to every generation, and the preceding one can have no right to bind it up from posterity.” Smith’s wisdom was often quoted by Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States and the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, the founding 1776 statement of the nation.

Progressive taxation - with those with the broadest shoulders paying more proportionately - is a fundamental principle of tax fairness, endorsed by a succession of tax commissions in a variety of countries. Achieving this requires, as the Nobel Laureate James Meade argued in his 1978 tax report, “that wealth itself should be included in the base for progressive taxation”.

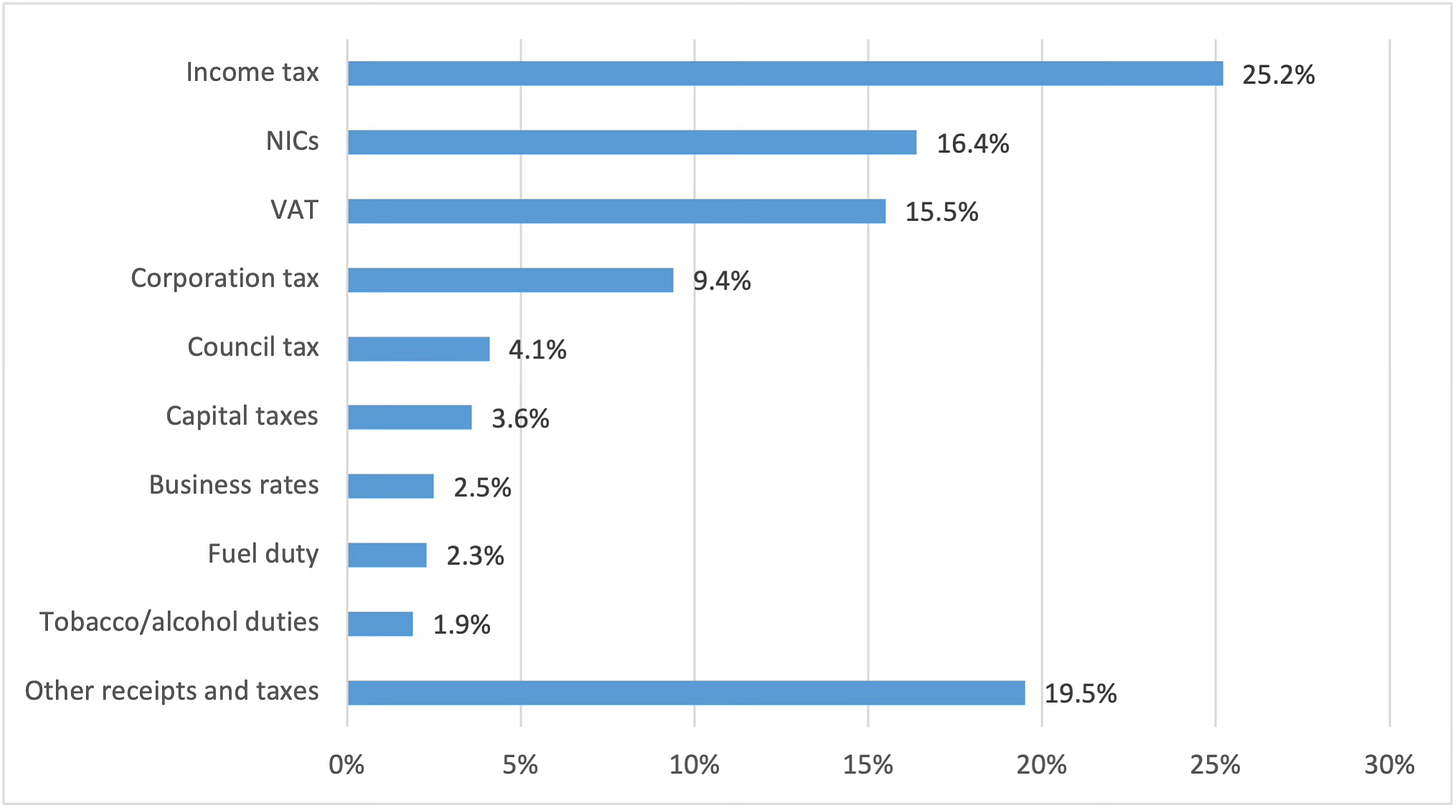

Despite this, calls for a higher share of inheritance to be socialised through taxation for the benefit of all are usually met with outrage by the popular media and sections of the political classes. As a result, only 3.7 per cent of deaths in the UK result in an inheritance tax charge. This compares with 10 per cent in Germany, and 9.3 per cent in Japan. As seen in chart 2, capital taxes, including inheritance, make a tiny contribution to the public purse.

A modest and phased shift to capital taxation would help to reduce the illiquid and passive role played by wealth holdings. Even modest rates would release resources for social reconstruction that would otherwise play a negative economic role. An important effect of higher taxes on top layers of wealth, for example, would be to weaken the volume of what the Italian-born radical journalist and future British MP, Leo Chiozza Money, called ‘wanton extravagance’, extreme levels of luxury spending on “non-productive occupations and trades of luxury, with a marked effect upon national productive powers”. One of the most damaging effects of lowly taxed wealth concentration is the way resources are steered away from meeting high social value basic needs to feed the often low social value demands of the rich. Hence the rising social crises facing affluent countries.

One of the most urgent tasks facing Britain is the need to rebuild its broken public services. Yet an effective strategy for reconstruction, to meet the growing needs of an ageing population, and strengthen fiscal resilience, needs to harness, through taxation, a little more of the country’s ill-used and immense private wealth base.

Stewart Lansley is a visiting fellow at the University of Bristol, a Council member of the Progressive Economy Forum, and the author of The Richer, The Poorer: How Britain Enriched the Few and Failed the Poor, a 200 year history.

Interesting article; there is little doubt that we need to rebalance wealth inequality but I worry that, as usual, the people who will suffer are those of us at the bottom end whilst those at the top pay accountants and lawyers to ensure they avoid paying. My father paid his taxes all his life and recently left me a modest sum which will help me buy my own property when my husband and I part company soon and split the proceeds of our home. I'm way too old to get a mortgage and am running out of employment opportunities. Why should I pay tax on monies my father earned and has already paid tax on? Why shouldn't my sister invest in property to help build a pension for herself, when her employment hasn't come with pension opportunities? What you are proposing runs the risk of penalising those of us that have struggled all our lives, and whilst dealing with the death of a parent, have to worry about what it's going to cost us.

Hi

Interesting read. Useful info for political conversations and campaigning. What’s included in the bottom row of chart 2? ‘Other taxes and receipts’?