Three Tory Tribes?

Our new report on the attitudes of 2019 Conservative voters to wealth finds that almost all are concerned about the reality or the impacts of wealth inequality

Background

In May 2023 we published National Wealth Surplus, a report based on a nationally representative opinion poll conducted by Opinium in April. This explored how attitudes to wealth, and wealth inequality, vary depending on how the wealth is acquired, and what people think about fairness questions (such as opportunity, luck and taxes) in relation to high net worth individuals (people with net wealth of £10 million or more).

One of the findings was that there was a high degree of consensus across the political divide. For example, the same proportion of 2019 Conservative voters and the general public (79%) agreed that the wealthy don’t contribute their fair share of taxes, while a similar proportion were concerned about the influence of the wealthy on politics (72% of 2019 Conservative voters, 75% of the general public). A high proportion of 2019 Conservative voters were also concerned about wealth inequality in the context of poverty in the UK (61%, compared to 68% of the general public).

We commissioned some additional statistical analysis of our polling data from two experts (Susie Mullen and David Dipple), to address three questions about how people think about wealth inequality, with a particular focus on 2019 Conservative voters:

What are the variables that are common to people in the UK who are concerned about wealth inequality?

Are there one or more groups of 2019 Conservative voters who are concerned about wealth inequality?

Which aspects of wealth inequality are 2019 Conservative voters more concerned about?

Findings

The statistical analysis found that, looking at the UK population as a whole, there isn’t a single group or set of variables that identify a group for whom wealth inequality matters, because wealth inequality matters to almost everyone (including Conservative voters), either in principle or because of its practical consequences.

Looking at 2019 Conservative voters in detail, a Principal Component Analysis identified three distinct groups:

Principled objectors (57% of 2019 Conservative voters), who are concerned about people not having equal opportunities to accumulate wealth, and about some enjoying wealth while others live in poverty

Pragmatic consequentialists (22% of 2019 Conservative voters), who are not worried about wealth inequality per se but are very concerned about some of the consequences - in particular that the wealthy have more influence over the political system and that they are not contributing their fair share of taxes

Frustrated meritocrats (21% of 2019 Conservative voters), who believe ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth (and so, by implication, that the UK is not a meritocratic country)

In other words, 78% of 2019 Conservative voters (the principled objectors and frustrated meritocrats) are exercised about wealth inequality in the UK, because of the absence of at least one of three fair necessities:

Fair essentials - a guarantee that everyone can meet their basic needs, no matter what

Fair opportunities - reduced inequalities so that everyone has truly equal chances in life

Fair rewards - a labour market that rewards everyone fairly for their contributions to our society

Meanwhile, the other 22% of 2019 Conservative voters are not worried about wealth inequality in and of itself, but are worried about the consequences of wealth inequality on the other two fair necessities:

Fair exchange - a fair and effective tax system that supports high quality public services for everyone

Fair treatment - equal social and political status for everyone, and more help for people who need it

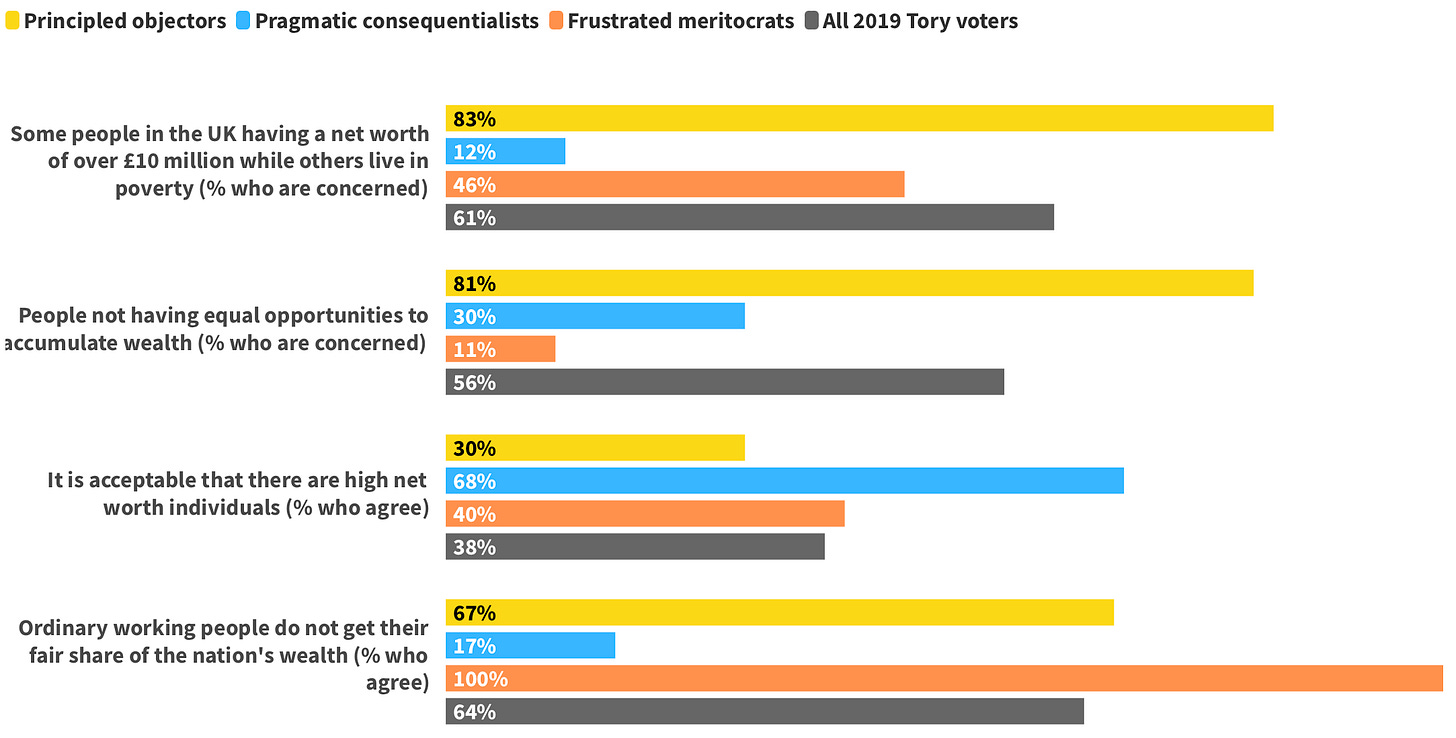

The graph below, which shows the proportion of people in each group who agree with (or are concerned about) each of the statements in the survey, demonstrates that there are clear differences between the three groups in terms of their views:

More than 80% of principled objectors are worried about inequality of wealth distribution and of opportunities to accumulate wealth. By contrast, pragmatic consequentialists are not concerned about the inequality of wealth distribution, and 68% of them think it is acceptable that there are high net worth individuals – much more than either of the other groups. Meanwhile, all frustrated meritocrats think that ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth, although they are not concerned about people having equal opportunities to accumulate wealth.

However, all three groups are concerned about the tax and political implications of wealth inequality:

When it comes to the views of the three groups about different ways of earning wealth (see the original report for more information about each of the seven ‘characters’), we find that, broadly speaking, principled objectors and frustrated meritocrats are somewhere between the average UK respondent and the average 2019 Conservative voter, while pragmatic consequentialists are generally further away than the average 2019 Conservative voter from the average UK respondent. However, these generalisations hide some interesting nuances. For example, frustrated meritocrats are very relaxed about the fairness of people inheriting money from parents who have earned their wealth (’new-money heirs’), but very exercised about the fairness of people inheriting money that has been in the family for generations (’old-money heirs’).

An analysis of voting intention suggests that 60% of pragmatic consequentialists will vote Conservative in the next election, compared to 50% of frustrated meritocrats and 41% of principled objectors. Most of those who indicated that they won’t vote Conservative are unsure who they will vote for, but principled objectors are more likely to vote for Labour (32% of principled objectors who said that they would not vote Conservative said they would vote Labour, compared to 22% for frustrated meritocrats and 12% for pragmatic consequentialists).

Discussion

The sample sizes in this research are not sufficient for us to draw firm conclusions from them alone1. However, there is plenty of other research that backs up the findings of this analysis. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies noted in 2021 on the basis of research by the Policy Institute at King’s College London, Britons are divided about whether hard work or factors outside people’s control have more influence on life chances, splitting into three similarly sized groups: ‘individualists’, ‘structuralists’ and those in the middle. However, 80 per cent of Britons are concerned about inequality - and this excludes those people who are concerned about some of the consequences (but not the mere fact) of inequality.

One could argue that many of the principled objectors are more worried about poverty than wealth (and concerns about poverty have increased in recent years, in particular among Conservative and Leave voters, partly due to COVID making poverty more obvious and visible for many people in their own neighbourhoods). But what if wealth inequality is itself a driver of poverty? Even before COVID, the LSE pointed to “a greater concentration of income and wealth, [with] fewer resources to be shared among the rest of the population and less concern for low-income households.” Reviewing the impact of the pandemic on inequality, the IFS found that “wealth inequality is likely to have increased between the poorest households and the rest of the population”. The causal relationship between wealth inequality and poverty is not widely understood, but if reducing wealth inequality is effective at tackling an issue (poverty) that many are concerned about, then it should be a priority.

As research by Ben Ansell at Oxford and Bobby Duffy et al at King’s College London (both summarised here) has shown, many people (including a majority of Conservative voters) are ‘individualists’, who believe that life outcomes are determined by individual effort more than by structural factors, and often think about fairness at a more individual than societal level. However, concerns about the consequences of wealth inequality offend both individual and societal conceptions of fairness, which perhaps explains how widespread those concerns are among Conservative voters.

Our survey in April only asked about the tax and political consequences of wealth inequality. But many Conservative voters are also worried about other consequences of wealth inequality (even if they do not necessarily see them as such), including wasted opportunity, the high costs of social problems such as poor health and crime, and a sharp decline in levels of social cohesion and trust.

There is, of course, a difference between concern about inequality and support for action by the government to address it, especially if doing so requires higher levels of tax and spend, and support for redistribution is reliably many percentage points lower than levels of concern about inequality. None of our three groups of 2019 Conservative voters support increasing redistribution in general (41% in favour overall, rising to 48% among principled objectors), or raising taxes a lot and spending much more on health and social services (32% in favour overall, rising to 36% among principled objectors). However, 64% of 2019 Conservative voters think the government should be doing more to tax high net worth individuals, with majorities in all three groups (66% of principled objectors, 62% of frustrated meritocrats and 52% of pragmatic consequentialists).

Some of our findings on levels of concern about inequality do not exactly correspond to some of the answers that we received when we asked about views of different ways of acquiring wealth in the same survey. For example, few people think that accumulating £5 million by being an entrepreneur, or a landlord, or even by inheriting it, is fundamentally unfair, even if they acknowledge that some of these routes to wealth owe more to luck than to merit and that they are not available to everyone simply through hard work. Our hypothesis is that, when thinking about specific ways of acquiring wealth, people are weighing up fairness considerations from a ‘fair process’ perspective, whereas when asked about levels of concern about wealth inequality, they are thinking more about ‘fair outcomes’. People are exercised about ‘unfair’ inequalities, but inequalities can be unfair as a result of their scale and their consequences, even if their causes are not universally seen as unfair.

Implications

Not everyone sees wealth inequality as intrinsically unfair. However, it has fairness consequences that concern almost everyone, regardless of their political leanings. Building support for action to tackle wealth inequality among right-of-centre audiences should therefore focus on those negative consequences or externalities, more than on the fact of wealth inequality per se. It should make a positive case for action, which may not always be framed explicitly in fairness terms. For example, reform of the taxation system, the housing market, the education or social care sectors or the social security system can be couched variously in terms of the benefits for prosperity (for individuals, businesses and society), opportunity and freedom (in the positive sense of capabilities and flourishing), security (economic and personal), and a healthier and more vibrant democracy. Reduced wealth (and, more broadly, socio-economic) inequality is the intermediate point of the causal chain, but does not need to be central to the argument that is being made; neither does fairness need to be the main benefit that is being sold.

There is also a need to increase awareness of some of the causal factors that are at play. In particular, while people seemingly don’t mind the rich getting rich if it doesn’t affect them, the reality is that it does affect them. Property ownership rates are falling, and families and the government are accumulating increasing levels of debt while the wealthy are accumulating assets. The fact that so few people are aware of this dynamic is a severe and urgent problem for our society, economy and democracy, which needs to be addressed rapidly.

On a positive note, however, the public are not as fatalistic about the potential for change as many in politics and the media think they are. On the contrary, the vast majority of Britons believe that the government has both the capacity and the responsibility to intervene in order to improve their lives, and an expectation that this will happen.

At the same time, we know that Conservative MPs (and party members) are in most cases well to the right of public opinion, including the opinions of Conservative voters, on economic issues (see, for example, King’s College London on ‘May’s Law’, and John Burn-Murdoch in the FT).

Politicians are constrained by economic reality, by their own ideological beliefs and by a reactionary media, but it would be a tragedy if they were also unnecessarily held back by a misapprehension that the public did not support bold policies that have the potential to be both transformative and popular.

For more discussion of these issues, see the recording of our webinar on public attitudes to wealth on 23 May 2023 with Polly Toynbee, Gary Stevenson and Dr Lucy Barnes. I’ll also be taking part in a webinar hosted by Patriotic Millionaires UK on tackling extreme wealth (how much is enough?), TOMORROW, 13 June, at 1pm UK time, for which you can register here.

The detailed statistical analysis was carried out on a sub-sample of 564 people who voted Conservative in 2019, from a total survey sample of 2,053 UK adults (April 2023). Of these 564, 323 people were identified as ‘principled objectors’, 126 as ‘pragmatic consequentialists’, and 115 as ‘frustrated meritocrats’. All respondents in the original survey were shown an information box in the middle of the survey about the scale of wealth inequality in the UK (showing that the wealthiest 20% of households in the UK own 63% of all wealth while the poorest 20% own 0.6%).